By Simon Moore, MD CCFP FCFP (biography and disclosures) Disclosures: Dr. Simon Moore is the Physician Lead for UBC CPD Cannabis Education for Health Care Providers series. He is a member of an advisory board for The Review Course in Family Medicine Inc. (includes Vital FM Update). He has received honoraria from The Review Course in Family Medicine, Vital FM Update, Seymour Clinic (clinical work), Doctors of BC, UBC CPD, BCCFP, UBC, Fraser Health. FVCPAA, fees transferred to charity. Mitigating Potential Bias: Recommendations are consistent with published guidelines such as the Canadian Simplified Guideline on cannabis. Recommendations are consistent with current practice patterns as determined by our expert committee. Discussion is of resources developed by committee or by other organizations which is based on published and/or peer-reviewed data. Treatments or recommendations in this article are not in direct financial relationship to products/services/treatments involved in disclosure statements. Content of the tools and educational resources was approved by a multidisciplinary committee which also mitigated any conflict for the content.

What I did before: Dodged the question

Since 2016, Health Canada has directed patients to clinicians like me to obtain authorization for cannabis. When this happened, I used to reply: “I don’t prescribe that. There isn’t much evidence.”

Typically, that was the end of it. Even if I tried to explore their symptoms further, my rapport with the patient had gone up in smoke. I felt like I was in an awkward position. It turns out, I was not alone.

A 2019 systematic review [1] of 26 studies (four from Canada) concluded that there is a “unanimous lack of self-perceived knowledge” among practitioners, even though they generally support medicinal cannabis use. So, I was thrilled when the first of two major resources was released in 2018 and addressed this gap.

What changed my practice

1. Practical Cannabis Tool #1: The Guideline

The 2018 Simplified Guideline for Prescribing Cannabinoids in Primary Care [2] is a comprehensive summary of the evidence to date and is endorsed by the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC).

Evidence: The 4 conditions

It concluded that evidence exists for pharmaceutical cannabinoids (nabilone capsules or nabiximols spray) as a third- or fourth-line option for:

- Palliative pain

- Neuropathic pain

- Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting

- Spasticity in multiple sclerosis or spinal cord injury

View Figure 1. Medical cannabinoid prescribing algorithm

View Figure 2. Neuropathic pain: Pharmacotherapy treatment. The Happy-face Diagram from the Simplified Guideline (2) with an easy-to-understand happy face diagram showing harms and benefits of various analgesics. I’ll never forget one patient who approached me for cannabis. After looking at this tool from the guideline, they pointed at amitriptyline and asked, “can I have a prescription for this instead?”

If you like this happy-face diagram, here’s another resource that’s even more likely to make you smile: https://pain-calculator.com/[3] from the PEER group has even more similar evidence-based diagrams.

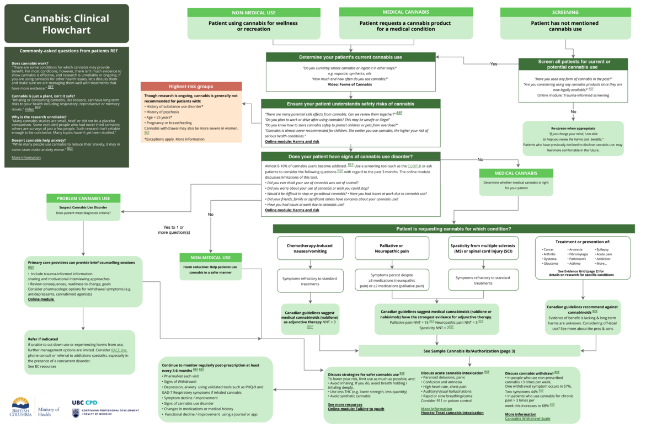

2. Practical Cannabis Tool #2: The Cannabis Clinical Flowchart

While the Simplified Guideline was a great tool for patients with one of those four conditions, it didn’t provide much guidance for the patients who ask me, “What about cannabis for anxiety? Or insomnia? Or arthritis?”

The Ministry of Health recognized this challenge and partnered with UBC CPD to create relevant education and point-of-care resources.

When I was approached to help with this project, I was reluctant because at that time I had never actually prescribed cannabis. Even more embarrassing was what happened when I mentioned that at one of our first planning meetings: I was quickly informed by our expert panel that dried cannabis is “authorized” and not prescribed.

Fortunately, the experts were more than willing to share their experience, and ultimately, we created a tool with no industry sponsorship:

The Cannabis Clinical Flowchart [4] is a one-stop birds-eye view that helps clinicians navigate common cannabis concerns. For example, it can be used to help at the bedside with:

- Non-medical use: Your patient is using cannabis recreationally;

- Medical use: A patient asks for cannabis for a medical condition, both guideline-based and for conditions beyond the guidelines; and

- Cannabis use disorder: You suspect a patient is struggling with problematic use.

Cannabis Sample Cannabis Prescription & Authorization [5]

Fill in the blanks for cannabinoid pills or sprays, or an authorization for dried cannabis. Dosing, titration, and expert tips are built right in. Note: to gain full access, learners must sign up for UBC CPD’s Cannabis Education for Health Care Providers online course.

Figure 2: Yet another cheat sheet in the resource: UBC CPD’s Sample Cannabis Prescription & Authorization [5], complete with pre- and post-checklists and clinical tips.

Cannabis Education for Health Care Providers free online course [6]

Learn to confidently address patient questions and explore best practices in cannabis prescription/authorization at your own pace. Chock full of clinical tips and helpful resources, this course is accredited for 1.5 Mainpro+/MOC Section 3 credits.

Cannabis Education for Health Care Providers virtual workshops [7]

Learn how to prescribe/authorize cannabis through real-life case studies under expert guidance. Practice using featured resources to support you in your patient interactions. Accredited for 4.0 Mainpro+ credits.

What I do now

Now, when a patient asks me about cannabis, I no longer suffer from dizziness, dry mouth, and paranoia.

Instead, I:

- Find out Why?

If today’s visit has been busy I’ll rebook and promise to discuss it in detail at the next visit. - Pull out the flowchart

…and work through the steps with the patient. - Discuss and prescribe (or authorize) confidently

Even if the evidence doesn’t fully support cannabis for my patient’s condition, these tools help me practice in an evidence-limited landscape while understanding what our medical regulators expect [8]. I can now explain the potential harms and benefits, avoid high-risk situations, consider a safe and reasonable dose, and complete the required pre-prescription steps and post-prescription monitoring.

References

- Gardiner KM, Singleton JA, Sheridan J, Kyle GJ, Nissen LM. Health professional beliefs, knowledge, and concerns surrounding medicinal cannabis – a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(5):e0216556. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216556 (View)

- Allan GM, Ramji J, Perry D, et al. Simplified guideline for prescribing medical cannabinoids in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(2):111-120. Accessed October 16, 2020. (View)

- Pain Calculator. Patients Experience Evidence Research (PEER). Accessed October 16, 2020. (View)

- Cannabis Clinical Flowchart. The University of British Columbia, Faculty of Medicine, Division of Continuing Professional Development (UBC CPD). Accessed October 16, 2020. ( View)

- Sample Cannabis Prescription & Authorization. The University of British Columbia, Faculty of Medicine, Division of Continuing Professional Development (UBC CPD). Updated October 6, 2020. Accessed October 16, 2020. (View*)

- Cannabis Education for Health Care Providers online course. The University of British Columbia, Faculty of Medicine, Division of Continuing Professional Development (UBC CPD). Accessed October 16, 2020. (View)

- Cannabis Education for Health Care Providers virtual workshops. The University of British Columbia, Faculty of Medicine, Division of Continuing Professional Development (UBC CPD). Accessed October 16, 2020. (View)

- Practice Standard: Cannabis for Medical Purposes. College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia (CPSBC). November 4, 2016. Updated February 12, 2020. Accessed October 1, 2020. (View)

- Authorizing Dried Cannabis for Chronic Pain or Anxiety: Preliminary Guidance from the College of Family Physicians of Canada. College of Family Physicians of Canada. 2014. Accessed October 16, 2020. (View)

- The Highs and Lows of Medical Cannabis. Alberta College of Family Physicians. October 15, 2018. Accessed October 16, 2020. (View)

- Crawley A, LeBras M, Regier L. Cannabis: Overview. RxFiles. Accessed October 27, 2020. (View)

- Cannabis and Driving. Ontario Medical Association. Accessed October 27, 2020. (View)

- Bertram J, Cirone S, Radakrisnan A. Non-Medical Cannabis. Centre for Effective Practice (CEP). Accessed October 27, 2020. (View)

- Fischer B, Russell C, Sabioni P, et al. Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines (LRCUG): an evidence-based update. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(8). doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303818 (View)

*To gain access to the interactive and most up to date versions of these documents, learners are encouraged to access the free Cannabis Education for Health Care Providers online course.

Additional Reading & Useful Tools:

- CFPC Preliminary Guidance: Authorizing Dried Cannabis for Chronic Pain or Anxiety [9] (2014): An updated version of this resource is expected to be released in the near future.

- CPSBC Practice Standard: Cannabis for Medical Purposes [10] (2020): Tips from the practice standard, plus many more tools[11] [12] [13] [14] [15] are integrated into the UBC CPD Cannabis Clinical Flowchart and Sample Cannabis Prescription & Authorization.

- UBC CPD Emerging Evidence for Medical Cannabis: Summary Grid: Summary of emerging evidence for seven medical conditions not covered in the CFPC Simplified Guideline for Prescribing Cannabinoids in Primary Care. Note: to gain access, learners must sign up for Cannabis Education for Health Care Providers online course.

- Patient Handout: Appendix to CFPC Simplified Guideline for Prescribing Cannabinoids in Primary Care.

Good topic important for primary care.

Love the charts and approach.

In Figure One there appears to be a typo in the Neuropathic Pain evidence summary box. The listed NNT for neuropathic pain is 3, which would actually imply it is the most effective pharmaceutical option. The listed reference, Allan et al 2018 guideline, contains absolute effect sizes and NNT estimates in table 1, which identifies the outcome of 30% improvement in neuropathic pain scale as providing an NNT of 11 or 14, depending on inclusion or exclusion of cancer studies. Either way, NNT 11 is very different effect size than NNT of 3, as 3 implies 33% of patients improve on drug over placebo, and 11 implies 9% of patients experience this improvement. Hopefully this typo can be easily fixed, as I suspect this algorithm will be used by many clinicians in the coming months.

As a secondary comment, the NNT of 15 quoted for palliative pain is transcribed correctly, but the source reference specifically notes it as a Non Statistically Significant (NSS) finding, with Very low quality evidence, perhaps NSS could be added to indicate the tenuous nature of this estimate.

Nice resources! A little proofreading to take this from good to great ;^) The previous commenter already pointed out the most important issue – NNT errors. There also seem to be some missing links within the flow chart itself – to the online modules and video?; and some redundant wording in this heading “Cannabis Sample Cannabis Prescription & Authorization”…

I found this to be helpful and it may well be useful in practice.

Thank you for this. I am giving a talk later this month on the use of cannabis in long term facilities as Interior Health has begun to accept patients’ use, and will definitely provide this as a resource.

A few thoughts.

1. The answer to why the research is unreliable is a bit sugar coated and does not mention the previously illegal nature of cannabis and how cannabis research was restricted. It wouldn’t hurt to mention that it is more difficult to study cannabis in Canada now than prior to legalization. I am the qualified investigator for an RCT of cannabis for PTSD symptoms and the hurdles are immense. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/canada-cannabis-research-barriers-1.5326667

2. Under “Strategies for safer cannabis use”, you suggest “Avoid inhaling”. This doesn’t generally produce the desired effect. I might suggest “Avoid smoking or vaping”.

3. The side effects that you list for CBD come from the Epidiolex monograph, which recommends doses of 5-20 mg/kg/day. These doses, in excess of 500-1000 mg/day have been found to be associated with these complications. Given that the cost of CBD is approximately $0.1/mg, very few patients will be able to afford such doses. Few patients in my practice take more than 60 mg/day and I have not seen the degree of reported side effects that you are suggesting.

4. There seems to be a typo above the “Sample Cannabinoid Prescription” where the arrows have been interchanged – “Dried Cannabis or Cannabis Oil” and “Nabilone or nabiximols”

5. On the topic of nabiximols, this is an expensive way to get an equal mixture of THC and CBD to a patient via an alcohol-based vehicle that is notorious for causing buccal irritation. A number of licensed producers make an equivalent mixture of THC and CBD in a carrier oil that can also be delivered by buccal spray and is cheaper.

6. Under suggested starting dose, “2-2.5 mg of CBD+/-THC” is a bit unclear. Dosage should be specified as the THC component, which is usually what causes most side effects. I would potentially start lower, at 1 mg THC, especially in elderly patients. My practice is to match this with at least as much CBD or more, as this has been speculated (little firm evidence) to decrease the “high” effect of THC.

This article is very interesting. I especially like the happy faces diagram. I would like to use that with clients. I work in mental health and addictions and a lot of clients relied on marijuana for pain management of various conditions. The happy faces scale could be useful in swaying people from the conviction that they need to smoke or ingest cannabis, or use opioids.