Authors

Dr. Mel Krajden (biography and disclosures) and Dr. Jim Gray (biography and disclosures)

Disclosures: Mel Krajden OBC, MD, BSc, FRCPC: received funding from Roche, Hologic, Siemens, and Abcellera for contracts unrelated to this work. Mitigating potential bias: contracts were unrelated to this work and recommendations are consistent with current guidelines. James R. Gray MD, CCFP, ABIM, FRCP(C): BC Guideline protocol advisory committee member. Mitigating potential bias: recommendations are consistent with current guidelines.

What I did before

The World Health Organization (WHO) observes July 28th as World Hepatitis Day and aims to eliminate Hepatitis B and C by 2030.1 The Pan-Canadian Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections (STBBI) Framework for Action released in 2018 echoes this goal and calls for 80% of eligible people in Canada to receive hepatitis C (HCV) treatment by 2030.2 In June 2021, the British Columbia (BC) Minister for Health, the Honourable Adrian Dix stated that the BC government is committed to achieving this HCV elimination goal by 2030.3

In order to achieve these HCV elimination goals by 2030, high rates of testing and diagnosis are essential. Previously, HCV screening was mainly based on the presence of risk behaviours, such as a history of injection drug use/sharing of drug injecting paraphernalia or receiving blood products prior to 1992. HCV treatment has changed considerably over the last decade, newer medications were expensive, poorly effective, and difficult to tolerate. As a result, they were initially introduced with disease stage treatment eligibility restrictions. However, new therapies are well tolerated, require 8 to 12 weeks of treatment, are publicly funded in BC, and have infection cure rates of about 95%.4

Despite this, as of 2019, the number of people with untreated HCV infection in BC (including vulnerable populations and those born between 1945-1965) was an estimated 20,922.5 There are numerous negative health outcomes and financial burdens on the health care system associated with untreated HCV. For example, untreated cases can progress to cirrhosis, liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma, or require liver transplantation and develop comorbidities such as renal failure or type 2 diabetes, or co-infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B (HBV).6

What changed my practice

The Guidelines and Protocol Advisory Committee (GPAC) in collaboration with the BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) revised the Viral Hepatitis Testing guideline, which was published on May 26th, 2021. Key recommendations specific to HCV include:

- Curative treatments (> 95 % effective) are available for those who have HCV infection.

- Patients known to have HCV infection, but who have not been previously treated and cured, should be recalled and engaged into care for HCV treatment.

- One-time HCV testing for the birth cohort 1945-1965 can be considered.

- One-time HCV testing for immigrants from endemic areas is recommended.

- Annual HCV testing for susceptible individuals with ongoing risks for HCV infection or reinfection is indicated.

- Treatment providers must establish a respectful, trust-based relationship with all patients, and need to consider HCV treatment within a holistic wellness framework.

- Where appropriate, individuals who have ongoing risks of HCV infection could benefit from further support and enrolment into comprehensive care (e.g., opioid agonist therapy, mental health and addiction services, alcohol reduction).7

What I do now

Screening

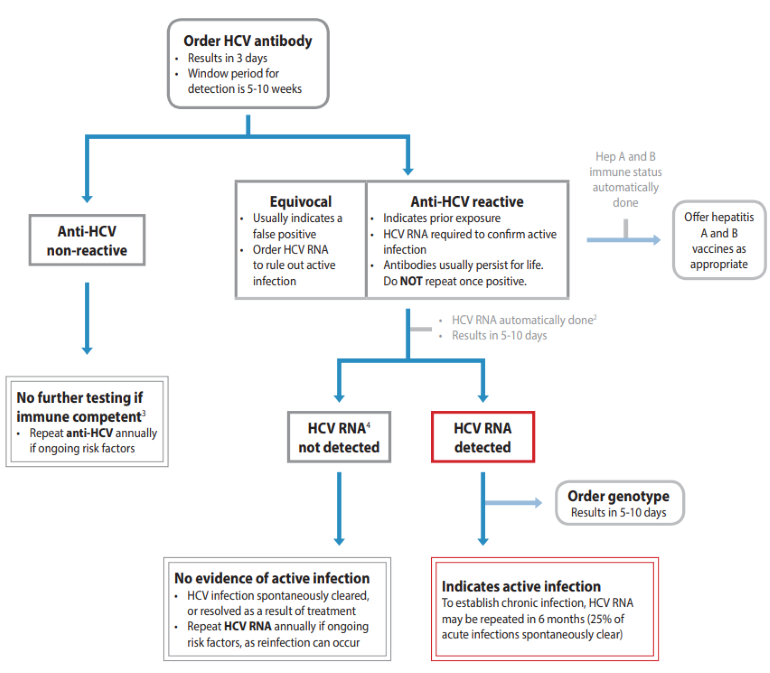

Screening for HCV infection and confirming which patients require treatment is more simplified now, since the introduction of HCV RNA reflex testing in BC in January 2020.8 Patient care greatly improves by diagnosing HCV infection from a single blood sample. This is due to decreasing time from screening to diagnosis and treatment, which decreases potential loss to follow-up and related morbidity and mortality.9 As the window period for detection of HCV antibodies in sera after initial exposure is 5-10 weeks, HCV RNA should be ordered as screening test if acute infection is suspected, as per BCCDC Communicable Disease Control Manual.

Figure 1: Hepatitis C Testing Guide7

Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee (GPAC). Viral Hepatitis Testing. Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee (GPAC); 2021. Available from www2.gov.bc.ca.

Management and Treatment

HCV treatment should be one part of a comprehensive approach to care, which should aim to address acquisition risk factors and comorbidities, and emphasize principles of harm reduction where appropriate. Ongoing drug and/or alcohol use are not contraindications to HCV treatment.7

There have been significant advances in HCV treatment because of well-tolerated all-oral treatment regimens called Direct Acting Antivirals (DAAs). More than 95% of patients with HCV infection receiving DAAs can be cured in 8-12 weeks of treatment and will experience very few side effects, compared to prior interferon/ribavirin treatment.10

Patients known to have HCV infection, but not previously treated and cured, should be recalled and referred for treatment. If a patient has HBV/HCV co-infection, refer to a specialist. Ongoing monitoring and/or treatment for HBV may be recommended to avoid reactivation of HBV infection.7

In BC, all patients with MSP coverage who have HCV infection are eligible for treatment with DAAs through the publicly funded drug plan (BC PharmaCare). In addition to tertiary centres, there are several other clinics across BC that provide HCV treatment and specialised support services. These clinics can be located through the BC Hepatitis Clinics map here: www.bccdc.ca.

Handouts for Patients

- “Hepatitis C: have you been tested?” patient handout

- HealthLinkBC: Hepatitis C Virus Tests

- BCCDC: Hepatitis Health Information

- GetCheckedOnline

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Combating Hepatitis B and C to Reach Elimination by 2030:advocacy brief. World Health Organization (WHO); 2016. Accessed July 27, 2022. (View)

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Reducing the health impact of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections in Canada by 2030: A pan-Canadian STBBI framework for action. Initiation of care and treatment. Published: June 29, 2018. Updated: July 9, 2018. Accessed July 27, 2022. (View)

- Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. Committee of the Whole – Section A Draft Report of Debates. 2nd Session, 42nd Parliament. Legislative Assembly of British Columbia; 2021. Accessed July 27, 2022. (View)

- Wilton J, Wong S, Yu A, et al. Real-world Effectiveness of Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir for Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C in British Columbia, Canada: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 Mar;7(3):ofaa055 (View)

- UBC Centre for Disease Control. Hepatitis C Cascade of Care in BC, 2019. UBC Centre for Disease Control; 2019. Accessed July 27, 2022. (View)

- Krajden M, Cook D, Janjua NZ. Contextualizing Canada’s hepatitis C virus epidemic. Can Liver J. 2018 Dec;1(4):218–30. DOI: 10.3138/canlivj.2018-0011. (View)

- BC Guidelines: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee. Viral Hepatitis Testing. BC Guidelines: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2022. (View)

- BCCDC Public Health Laboratory. BCCDC public health laboratory update: hepatitis C reflex testing. BC Centre for Disease Control, 2020. Accessed July 27, 2022. (View)

- Gin S, Buxton J, Janjua N, Krajden M, Bartlett S. Addressing inequities in care on the path to eliminating hepatitis C in BC. BCMJ. 2021;63(6):252. (View)

- Sachdeva H, Benusic M, Ota S, et al. Community outbreak of hepatitis A disproportionately affecting men who have sex with men in Toronto, Canada, January 2017–November 2018. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2019 Oct 3;45(10):262–8. DOI: 10.14745/ccdr.v45i10a03. (View)

Recent Comments