Michael J. Diamant, MSc, MD, FRCPC (biography and disclosures)

Disclosures: Received speaker or moderator fees from Novartis, Pfizer, and Astra Zeneca. Received consulting fees from HeartLife Canada and Bayer. Site co-investigator for trials sponsored by Bayer and AstraZeneca. Mitigating potential bias: All recommendations are consistent with published guidelines (mentioned or referenced in the article) and current practice patterns.

What frequently asked questions/gaps I have noticed

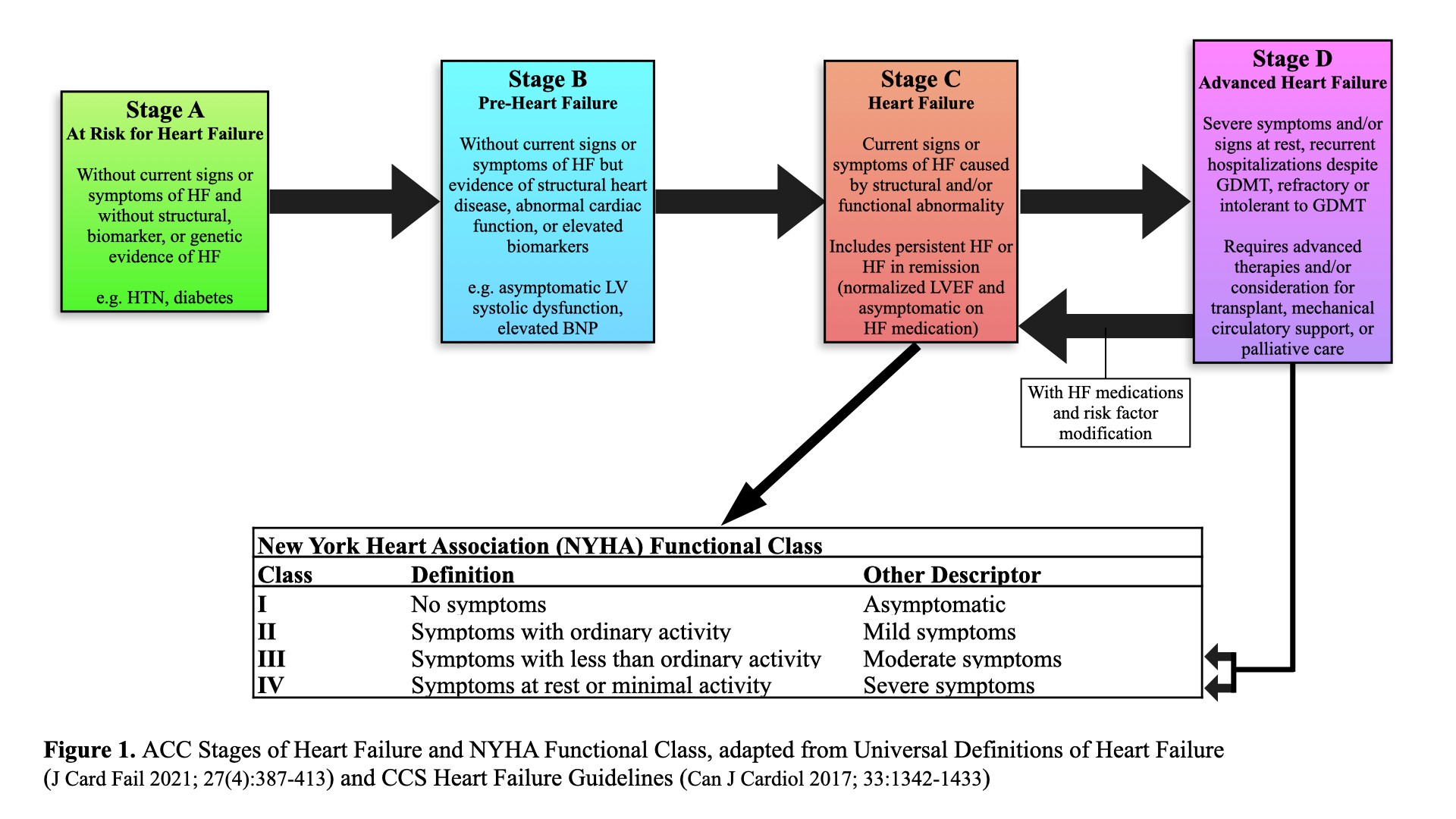

The prevalence of ambulatory patients with advanced or end-stage heart failure (HF) is increasing over time, and now comprises as much as 14% of all patients with HF1. Categorized by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association as Stage D HF (Figure 1), it is defined as “structural abnormalities of the heart and severe resting symptoms despite optimal medical, surgical, and device therapy.”2 Approximately 5% of patients progress from symptomatic or stage C HF to stage D each year.3 These patients have advanced symptoms (New York Heart Association [NYHA] Functional Class III or IV – see Figure 1), are at high risk of hospitalization and rapid deterioration and have a 1-year mortality of up to 50%.

Yet, a proportion may be eligible for advanced therapies, including durable mechanical circulatory support (MCS) and heart transplantation, that can change their trajectory and markedly improve long-term survival.1,2 Moreover, early referral (before patients deteriorate on inotropes or require short-term MCS) has been associated with improved post-transplant outcomes.4 In those not eligible for advanced therapies, referral to palliative care and advanced care planning can result in improvement of symptoms, functional status, quality of life, and depression/anxiety, yet patients are less frequently referred to palliative care than other end-of-life conditions.5-9 Some signs of advanced HF, such as inotrope-dependence and recurrent implanted defibrillator shocks, may prompt presentation to hospital, but less “obvious” signs may be present in chronically deteriorating outpatients. These are often missed, and patients are referred too late; this may be especially true of those from minoritized or racialized groups.10 Identifying and expeditiously referring ambulatory patients with advanced HF to the appropriate specialist is thus of the utmost importance, with different therapeutic interventions available based on eligibility, supplemental testing, and patient and program preferences.

Data that answers these questions/gaps

HF hospitalization is a critical event signifying high-risk patients at risk of declining health status. A recent Finnish study found each HF hospitalization is associated with 2.2–2.3 fold increase in cardiovascular (CV) death.11 As such, multiple guidelines and consensus statements have suggested that two or more HF hospitalizations should trigger a referral to a heart failure specialist.12-14

Progressive end-organ dysfunction can also be a sign of advanced HF in ambulatory patients and can manifest through abnormalities in kidney, liver, and/or lung function.

Kidneys:

Worsening renal function, defined in studies as an increase in serum creatinine of 26-44 umol/L or a 25% increase from baseline during follow-up without another cause, is primarily mediated through persistent venous congestion resulting in decreased renal perfusion.15,16 This has been associated with a 96% increased odds of mortality among HF patients.15

Liver:

Liver synthetic function can also be affected in HF. Chronic venous congestion can lead to centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis and bile stasis, which could, in turn, lead to bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis.17 In a CHARM trial substudy, a bilirubin >14 μmol/L was associated with a 21% increase in cardiovascular (CV) death or HF hospitalization.18

Lungs:

Pulmonary hypertension in the setting of established HF should also be seen as end-organ damage that can be suggestive of advanced HF. A Japanese study found that among ambulatory patients with dilated cardiomyopathies, the presence of pulmonary hypertension (defined as a mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥25 mmHg) was associated with >11-fold risk of CV death.19

In addition to acting as signs of advanced HF, kidney or liver dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension can also serve as complicating factors or potential contraindications to durable MCS and cardiac transplant.20,21 Their presence therefore merits referral to a heart failure specialist.

Persistent congestion despite escalating diuretics and/or persistent hyponatremia have been associated with adverse outcomes in HF.22 Additionally, an LVEF that remains ≤25% despite medical therapy, or intolerance (or new intolerance and hypotension, if previously on stable doses) of HF guideline-directed medical therapy, are other ominous signs indicative of advanced HF.22-24 Labs and risk scores may also be able to provide additional prognostic information in HF. Risk prediction scores, like the Seattle Heart Failure Model (SHFM) and the MAGGIC Score, incorporate many of the aforementioned risk factors of advanced HF and can provide a reasonably accurate estimate of 1-year survival that can aid in decision-making.12,22,24 Additionally, obtaining a natriuretic peptide level (BNP or NT-pBNP) can add incremental value for prognostication, even when added to risk prediction scores, as persistently high natriuretic peptides have been associated with poor outcomes.23,25,26

What I recommend (practice tip)

Patients with advanced symptoms and any of the above signs, and who do not have non-cardiac conditions that limit life expectancy or functional status, should be referred to an advanced heart failure specialist.10 The following is a link to a comprehensive list of Heart Function Clinics in British Columbia. At the present time, each clinic located at a tertiary cardiac centre includes cardiologists with training in advanced HF and transplant, and heart transplant and ventricular assist device services continue to be located at St. Paul’s Hospital. View cardiacbc.ca.

Additional reading

- Section 7.1.4 in the 2017 Comprehensive Update of the CCS Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure includes an extensive list of criteria to identify patients with advanced HF11: View.

- Alternatively, “I NEED HELP” is a simplified, peer-reviewed, and widely used mnemonic to help with bedside identification of advanced HF patients, and whose components reflect risk factors identified by international guidelines and consensus statements27: View.

- Lastly, risk prediction scores like the SHFM and MAGGIC Score can estimate 1-year mortality and long-term survival, and aid in decision-making and timing of referral.22,23 As a benchmark comparison, the estimated 1-year survival after a ventricular assist device or transplant in all-comers is approximately 85% and 85-90%, respectively.28,29 These scores can be accessed online (SHFM: View) or through medical calculation apps.

References

- Dunlay SM, Roger VL, Killian JM, et al. Advanced Heart Failure Epidemiology and Outcomes: A Population-Based Study. JACC Heart Fail. 2021; 9(10):722-732. DOI: 10.1016/j.jchf.2021.05.009. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

- Fang JC, Ewald GA, Allen LA, et al. Advanced (Stage D) Heart Failure: A Statement From the Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines Committee. J Card Fail. 2015; 21(6):519-534. DOI: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.04.013. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Kalogeropoulos AP, Samman-Tahhan A, Hedley JS, et al. Progression to Stage D Heart Failure Among Outpatients With Stage C Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2017; 5(7):528-537. DOI: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.02.020. (View)

- Barge-Caballero E, Segovia-Cubero J, Almenar-Bonet L, et al. Preoperative INTERMACS Profiles Determine Postoperative Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients Undergoing Emergency Heart Transplantation. Circ Heart Fail 2013; 6(4):763-772. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000237. (View)

- Diamant MJ, Keshmiri H, Toma M. End-of-life care in patients with advanced heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2020; 35(2):156-161. DOI: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000712. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, et al. Palliative Care in Heart Failure (PAL-HF) Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 70(3):331-341. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.030. (View)

- Bekelman DB, Allen LA, McBryde CF, et al. Effect of a Collaborative Care Intervention vs Usual Care on Health Status of Patients With Chronic Heart Failure. JAMA Interrn Med. 2018; 178(4):511-519. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8667. (View)

- Sidebottom AC, Jorgenson A, Richards H, Kirven J, Sillah A. Inpatient Palliative Care for Patients with Acute Heart Failure: Outcomes from a Randomized Trial. J Palliat Med. 2015; 18(2):134-142. DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0192. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Liu AY, O’Riordan DL, Marks AK, Bischoff KE, Pantilat SZ. A Comparison of Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure and Cancer Referred to Palliative Care. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(2):e200020. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0020. (View)

- Huusko J, Tuominen S, Studer R, et al. Recurrent hospitalizations are associated with increased mortality across the ejection fraction range in heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2020; 7(5):2406-2417. DOI: 10.1002/ehf2.12792. (View)

- Ezekowitz JA, O’Meara E, McDonald MA, et al. 2017 Comprehensive Update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure. Can J Cardiol. 2017; 33(11):1342-1433. DOI: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.08.022. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. Circulation. 2013; 128(16):e240-e327. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. (View)

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021; 42(36):3599-3726. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. (View)

- Damman K, Valente MAE, Voors AA, O’Connor CM, van Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL. Renal impairment, worsening renal function, and outcome in patients with heart failure: an updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2013; 35(7):455-469. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht386. (View)

- Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, et al. Importance of Venous Congestion for Worsening of Renal Function in Advanced Decompensated Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53(7):589-596. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.068. (View)

- Auer J. What does the liver tell us about the failing heart? Eur Heart J. 2012; 34(10):711-714. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs440.(View)

- Allen LA, Felker GM, Pocock S, et al. Liver function abnormalities and outcome in patients with chronic heart failure: data from the Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) program. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009; 11(2):170-7. DOI: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn031. (View)

- Hirashiki A, Kondo T, Adachi S, et al. Prognostic Value of Pulmonary Hypertension in Ambulatory Patients With Non-Ischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2014; 78(5):1245-1253. DOI: 10.1253/circj.CJ-13-1120. (View)

- Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: A 10-year update. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016; 35(1):1-23. DOI: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.10.023. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

- Walther CP, Niu J, Winkelmayer WC, et al. Implantable Ventricular Assist Device Use and Outcomes in People With End-Stage Renal Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7(14). DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008664. (View)

- Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, et al. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):1424-33. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. (View)

- Barlera S, Tavazzi L, Franzosi MG, et al. Predictors of mortality in 6975 patients with chronic heart failure in the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell’Infarto Miocardico-Heart Failure trial: proposal for a nomogram. Circ Heart Fail. 2013 Jan;6(1):31-9. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.967828. (View)

- Pocock SJ, Ariti CA, McMurray JJ, et al. Predicting survival in heart failure: a risk score based on 39 372 patients from 30 studies. Eur Heart J. 2013 May;34(19):1404-13. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs337. (View)

- Anand IS, Fisher LD, Chiang Y, et al. Changes in Brain Natriuretic Peptide and Norepinephrine Over Time and Mortality and Morbidity in the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val-HeFT). Circulation. 2003; 107(9):1278-1283. DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000054164.99881.00. (View)

- Khanam SS, Choi E, Son J, et al. Validation of the MAGGIC (Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure) heart failure risk score and the effect of adding natriuretic peptide for predicting mortality after discharge in hospitalized patients with heart failure. PLoS ONE. 2018; 13(11):e0206380. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206380. (View)

- Morris AA, Khazanie P, Drazner MH, et al. Guidance for Timely and Appropriate Referral of Patients With Advanced Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021; 144(15):e238-250. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001016. (View)>

- Baumwol J. “I Need Help”—A mnemonic to aid timely referral in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017; 36(5):593-594. DOI: 10.1016/j.healun.2017.02.010. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

- Hanke JS, Dogan G, Zoch A, et al. One-year outcomes with the HeartMate 3 left ventricular assist device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018; 156(2):662-669. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.01.083. (View)

- Khush KK, Hsich E, Potena L, et al. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult heart transplantation report — 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021; 40(10):1035-1049. DOI: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.07.015. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

Recent Comments