Authors:

Elina Liu MD (biography, no disclosures), Erin Morley MD (biography, no disclosures), and Anna Rahmani MD (biography and disclosures)

Disclosure for Dr. Anna Rahmani: Received funding for grants/research: University of Ottawa Blood Disease Center (not supported by pharmaceutical companies). Received financial payments: Pfizer: speaker honoraria. Servier: unrestricted educational grant for thrombosis clinic. Bayer: speaker honoraria.

Mitigating potential bias: Only published trial data is presented. Treatments and recommendations in this article are unrelated to products/services/treatments involved in the disclosure statement.

What frequently asked questions we have noticed

Each year, 1 in 6 patients with atrial fibrillation, or an estimated 6 million patients worldwide, will require perioperative anticoagulant management (1). An increasing number of atrial fibrillation patients are using direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in place of warfarin for stroke prevention. However, there has been uncertainty regarding perioperative management of DOACs, with significant variability noted in clinical practice. This can lead to potential harm with increased risk of thrombosis if a DOAC is held for too long versus increased risk of post-operative bleeding if interruption intervals are too short.

Common questions arising in daily practice include: What is the optimal timing for holding and restarting DOACs? Does the risk depend on the type of surgery? Should we use heparin for “bridging”? And are there changes in practice when spinal-epidural anesthesia is used?

The purpose of this article is to answer the aforementioned questions and better inform healthcare practitioners regarding safe practices for perioperative DOAC management.

Data that answers these questions

The PAUSE Trial was a multicenter international trial published in August 2019 to assess the safety of using a standardized protocol for the perioperative management of three DOACs: apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban (1). Patients included in the trial were >=18 years of age with atrial fibrillation, and CrCl >=25 mL/min for apixaban or >=30 mL/min for dabigatran or rivaroxaban.

The interruption and resumption intervals were determined in the protocol based on three simple variables: the type of DOAC, the prespecified bleeding risk of the procedure, and renal function. The bleeding risk of the procedure or surgery was determined by a pre-specified classification (Table 1). There were no changes to these intervals for patients on reduced dose anticoagulation.

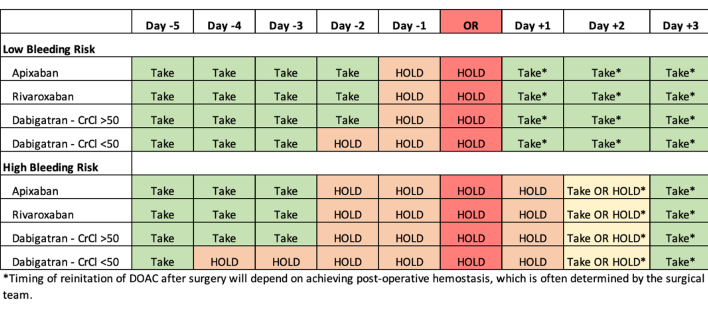

For dabigatran with CrCl >= 50 mL/min, apixaban, and rivaroxaban, anticoagulation was held for 1 day before low-bleeding-risk procedures (no DOAC on day -1), and for 2 days before high-bleeding-risk procedures (no DOAC on day -2 or day -1). For patients on dabigatran with CrCl < 50 mL/min, anticoagulation was held for 2 days prior to a low-bleeding-risk procedure (no DOAC on day -2 or -1), and for 4 days before a high-bleeding-risk procedure (no DOAC from day -4 to day -1) (Figure 1). The postoperative DOAC resumption schedule indicated that all patients undergoing low-risk procedures were to start anticoagulation on postoperative day 1, approximately 24 hours after the operation, and patients undergoing high-risk procedures were to start anticoagulation on postoperative day 2 or 3, as long as hemostasis was achieved. Patients at high risk for venous thromboembolism were permitted to receive prophylactic heparin after the procedure until DOACs were resumed.

The primary outcomes assessed in the PAUSE trial were major bleeding within 30 days and arterial thromboembolism, including TIA, stroke, and systemic embolism. In addition, pre-operative serum DOAC levels were measured, with <50 ng/mL considered an empiric target at which a procedure should be able to proceed safely.

3007 patients undergoing elective surgery, with a mean age of 72.5, were included in the trial, 42% of whom were on apixaban. The average serum creatinine for each arm was between 87.7 mmol/L and 94.1 mmol/L. A minimum of 30% of patients in each arm underwent high-bleeding-risk procedures, and 7.6% of patients received neuraxial anesthesia.

30 day postoperative rate of major bleeding was found to be 1.35% (95% CI 0%-2.0%) for apixaban, 0.9% (95% CI 0%-1.73%) for dabigatran, and 1.85% (95% CI 0%-2.65%) for rivaroxaban. The proportion of patients with major bleeding was largely powered by the high-bleeding-risk cohort. In patients with a high–bleeding-risk procedure, the rates of major bleeding were 2.96% (95% CI, 0%-4.68%) in the apixaban cohort, 0.88% (95% CI 0%-2.62%) in the dabigatran group, and 2.95% (95% CI, 0%-4.76%) in the rivaroxaban cohort.

Rates of arterial thromboembolism were consistently low and within the outlined safety targets. Preoperative DOAC treatment levels found that 90% of patients or greater achieved a level of <50 ng/mL, and specifically 98.9% of high-risk patients were lower than this threshold.

Though the 95% confidence interval for major bleeding exceeded the predefined safety upper limit of 2% in the rivaroxaban cohort, authors of the PAUSE trial felt overall that the rates of adverse outcomes found in this study were comparable to others. Therefore, the overall conclusion was that following a simple, standardized strategy without heparin bridging for perioperative management of DOACs was both safe and effective.

Of note, edoxaban was not assessed in this study. In addition, use of anticoagulation for the purpose of treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) was not included in the inclusion criteria, and therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to this patient population.

What we recommend (practice tip)

We recommend following the standardized perioperative DOAC management protocol outlined by the PAUSE trial.

- Hold rivaroxaban, apixaban, or dabigatran (if CRCL > 50) starting on day -1 prior to low-risk surgery or on day -2 prior to high-risk surgery.

- Hold dabigatran (if CRCL < 50) on day -2 prior to low-risk surgery, and day -4 prior to high-risk surgery.

- No heparin bridging is needed given the short and predictable half-lives of these agents.

- No routine anticoagulation testing is required pre-operatively.

- Resume DOAC on post-op day 1 for low-risk surgery if hemostasis is felt to be achieved.

- Resume DOAC on post-op day 2-3 for high-risk surgery if hemostasis is felt to be achieved and there are no contraindications like an epidural catheter placed for pain control.

- Be aware that in the setting of neuraxial anesthesia or very high-risk surgeries, Anesthetists/Specialists may choose a more conservative interruption period for DOACs.

- Patients at high risk for venous thromboembolism can receive prophylactic VTE therapy after the operation until DOAC therapy resumes.

- Of note, patients in the study had a relatively normal renal function, with serum creatinine between 87.7 mmol/L and 94.1 mmol/L for each arm; caution regarding how many days to hold pre-operatively and on reintroduction is warranted in patients with impaired renal function.

Thrombosis Canada has both a “clinical guide” and a “clinical tool” on perioperative management of DOACs. The clinical guideline features a protocol identical to that from the PAUSE trial. We recommend referring to both the Thrombosis Canada “clinical guide” and “clinical tool” on perioperative management of DOACs when any questions arise in daily clinical practice (Thrombosis Canada Perioperative Anticoagulant Management Algorithm).

The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) also published guidelines in April 2018 which included perioperative management of DOACs in the setting of neuraxial intervention. These guidelines are more conservative than those outlined by the PAUSE trial and Thrombosis Canada. Therefore, in the setting of neuraxial anesthesia or very high-risk surgery, the anesthesiologist may recommend holding the DOAC for a different period of time depending on their facility’s policies on perioperative DOAC management.

For questions or concerns regarding anticoagulation in the perioperative period unanswered by the aforementioned guidelines, including management in patients with borderline renal function, unclear surgical bleeding risk, or VTE patients, phone advice may be obtained from St. Paul’s Hospital Race Line for Thrombosis (604-696-2131 www.raceapp.ca).

References and Resources

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Duncan J, Carrier M, Le Gal G, Tafur AJ, et al. Perioperative Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Receiving a Direct Oral Anticoagulant. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1469–1478. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2431. (View).

- Horlocker TT, Vandermeuelen E, Kopp SL, Gogarten W, Leffert LR, Benzon HT. Regional Anesthesia in the Patient Receiving Antithrombotic or Thrombolytic Therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Guidelines (Fourth Edition). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(3):263-309. DOI: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181c15c70. (View with CPSBC or UBC).

- Narouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano D, Buvanendran A, De Andres J, Deer T, et al. Interventional Spine and Pain Procedures in Patients on Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications (Second Edition): Guidelines From the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(3):225-62. DOI: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000700. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Thrombosis Canada. Perioperative Anticoagulant Management Algorithm [Clinical Tool]. (View). Accessed Nov 15, 2021.

- Thrombosis Canada. NOACs/DOACs: Perioperative Management. Published April 30, 2019. (View). Accessed Nov 15, 2021.

- Spyropoulos AC, Douketis JD. How I treat anticoagulated patients undergoing an elective procedure or surgery. Blood. 2012; 120 (15): 2954–2962. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-415943. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC).

- Thrombosis Canada mobile and web apps: View to download. Accessed Nov 15, 2021.

Figure 1: Perioperative Direct Oral Anticoagulant (DOAC) Management Protocol. Adapted from Thrombosis Canada & Douketis et al. JAMA 2019. (Download)

Table 1:

Classification of surgery or procedures as high or low bleeding risk, from the supplemental index of

Douketis et al. JAMA 2019. (Download)

| High Bleed Risk Surgery/Procedures | Low Bleeding Risk Surgery/Procedures |

1) Any surgery requiring neuraxial anesthesia

2) Major intracranial or neuraxial surgery

3) Major thoracic surgery

4) Major cardiac surgery

5) Major vascular surgery

6) Major abdominopelvic surgery

7) Major orthopedic surgery

8) Other major cancer or reconstructive surgery

|

1) Gastrointestinal procedures

2) Cardiac procedures

3) Dental procedures

4) Skin procedures

5) Eye procedures

|

Does the no bridging apply to high risk AFIB patients. The average CHADS2 score in the Pause trial is 2.1

Hi Riley Hicks,

You are correct! You do not need to bridge patients on DOACs, even if their CHADS2 score is high, due to their predictable pharmacokinetics. Post-operatively, if patients are at a higher risk of thromboembolism, you may want to consider giving prophylactic doses of LMWH or a reduced dose of DOAC as early as POD1, as long as the surgical team feels that hemostasis is adequate.

I’m not sure I agree with putting colonoscopy under “Low bleeding risk”. A polypectomy is usually considered a high bleeding risk procedure because they bleed a lot.

If it is a colonoscopy withOUT polypectomy then yes, it would be low risk. However, there is no way to know ahead of time whether a polyp will be encountered or not. I suppose it’s possible to schedule a second colonoscopy with interruption of the DOAC, but that isn’t a very practical approach.