By Dr. Janet Simons (biography, no disclosures)

What gap I have noticed

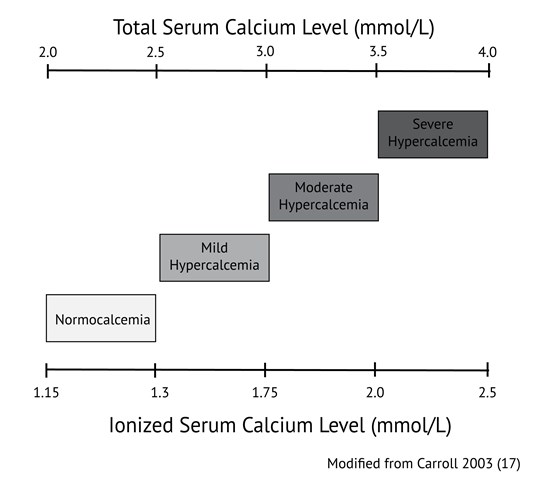

Calcium levels are commonly ordered in both primary and acute care in patients with a variety of signs and symptoms. Hypocalcemia (total calcium concentrations generally below 2.0 mmol/L or ionized calcium below 1.15 mmol/l) is usually related to dietary deficiencies or disorders of the parathyroid axis, such as in patients with previous surgery or autoimmune destruction of the parathyroid gland. Hypercalcemia (above 2.5 mmol/L total calcium or 1.3 mmol/L ionized) in primary care is commonly associated with dehydration, primary hyperparathyroidism, and malignancy such as multiple myeloma. When hypercalcemia is severe, generally defined as total calcium above 3.5 mmol/L or ionized calcium above 2.0 mmol/L, therapy should be initiated immediately. Values of calcium below this threshold but above 3.0 mmol/L total calcium or 1.75 mmol/L ionized are considered moderate hypercalcemia and patients with calcium values in this range may not need immediate therapy but should be monitored closely. Precise values of normal ranges and cut offs may vary between laboratories.

It remains common practice to apply the Payne formula (usually expressed as albumin-adjusted calcium (mmol/L) = total calcium (mmol/L) + 0.02 [40 – albumin (g/L)]) (1) to adjust total calcium. This correction is intended to enhance the ability of the total calcium concentration to serve as a marker of the physiologically relevant parameter, ionized calcium, in patients with hypoalbuminemia.

Since the original Payne paper, clinical use of this correction formula has spread such that many clinicians routinely apply this ‘correction’ to all total calcium measurements. This observation is supported by data available from Vancouver Coastal Health and Providence Health Care laboratories. In 2018, total serum calcium and albumin were ordered together 72% of the time, suggesting that many clinicians believe that serum albumin measurement is required in order to interpret total calcium concentrations.

There are a number of problems with the Payne formula. This formula was derived in 200 patients whom Payne considered to be unlikely to have abnormalities of ionized calcium, however 20% of the patients had hyperproteinemia secondary to multiple myeloma. Payne et al relied upon results from a single laboratory which used methodologies for the measurement of albumin and total calcium which are different from methods in routine use today. The formula was designed to transform the calcium results in those patients who had hypoalbuminemia so that the distribution of results would match the distribution of calcium results in the patients with normal serum albumin concentrations. There was no validation of the formula using ionized calcium, which was not measured.

What data addresses this gap

There is considerable evidence (2-12) that application of the Payne formula tends to misclassify the calcium status of patients and performs less well than simply evaluating uncorrected total calcium. Payne himself recently wrote a letter to the editor (13) in which he acknowledged that his original formula is not universally applicable, requiring modification for the specific albumin assay in use by a laboratory, and that any albumin-based adjustment will likely overestimate calcium in patients with renal failure. In renal failure, the albumin concentration is underestimated when uremia induced carbamylation of albumin reduces its detection by the assay (14). Attempts to derive a new formula (10-12) to improve upon the performance of the Payne formula have failed to find a correction which performs significantly better than unadjusted total calcium.

The physiological basis for the albumin adjustment is the theory that when albumin is reduced, the amount of calcium bound to albumin is also reduced, such that the total serum calcium may be low despite a normal ionized calcium concentration. However, this physiologic basis is belied by evidence that in hypoalbuminaemic states, the binding constant between albumin and calcium changes, and more calcium binds to each available gram of albumin (15). Formulae such as the Payne formula which assume a constant relationship between albumin concentration and the fraction of calcium which is bound to albumin are thus expected to overestimate ionized calcium in patients with low albumin. Several studies have borne out this tendency of correction formulae to overestimate ionized calcium.

Steen et al (2) found that in patients with albumin <30 g/L, 75% of patients classified as normocalcemic using the Payne formula in fact had hypocalcemia based on ionized calcium levels. Another study (3) found that adjusted calcium values derived by applying the Payne formula agreed with ionized calcium levels in only 55-65% of patients. In contrast, unadjusted total calcium correctly categorized 70-80% of patients. Agreement between adjusted calcium and ionized calcium was even worse for patients with renal impairment (eGFR<60 min/mL/1.73m2). The adjustment significantly overestimated calcium concentrations in these patients. A similar trend has been documented in critically ill patients in both the medical and surgical ICU settings (4-6).

The poor performance of the calcium correction has also been observed in the hypoalbuminemic geriatric population (7). Again, the correction impairs the sensitivity of the corrected result to detect true hypocalcemia. The more severe the hypoalbuminemia, the poorer the performance of the adjustment formula. This has also been demonstrated in stable hemodialysis patients (8-9).

Other studies (10-11) have sought to derive new formulae for the purpose of correcting calcium for albumin concentration. James et al (10) considered many possible formulae but ultimately concluded that if any adjustment is to be made to calcium to account for hypoalbuminemia, the adjustment formula must be locally derived.

Many of the studies above were done in hospital inpatients. Less data is available in outpatients, as ionized calcium is more difficult to measure in this population due to the requirement that specimens for ionized calcium be analyzed promptly after collection (16). However, a study which examined results from both inpatients and outpatients of a hospital and excluded critically ill patients (12) confirmed that unadjusted total calcium performs better than any of the available correction formulae (including those put forth by Payne and James) in ROC analysis compared to the ionized calcium gold standard.

What I recommend (practice tips)

Formulae to adjust total calcium for the albumin concentration should be abandoned. The use of these formulae overestimates ionized calcium in patients with hypoalbuminemia, causing false negatives for hypocalcemia and false positives for hypercalcemia. Measurement of ionized calcium is now relatively inexpensive and is available in most hospitals and many outpatient settings.

- Measurement of ionized calcium is recommended over total calcium when calcium homeostasis is in question.

- If calcium is ordered as a ‘screening’ test without specific clinical suspicion for a disorder of calcium homeostasis, it is reasonable to assess unadjusted total calcium. If this level is abnormal, confirmation with ionized calcium may be sought prior to further workup or therapy.

- Where ionized calcium is not available, total calcium should be assessed without the application of any correction formula.

- Order serum albumin only if clinically indicated for reasons other than adjusting total calcium.

References

- Payne RB, Little AJ, Williams RB, Milner JP. Interpretation of serum calcium in patient with abnormal serum proteins. Br Med J. 1973;4:643-646. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.4.5893.643. (View)

- Steen O, Clase C, Don-Wauchope A. Corrected calcium formula in routine clinical use does not accurately reflect ionized calcium in hospital patients. Canad J Gen Int Med. 2016;11(3):14-21. DOI: 10.22374/cjgim.v11i3.150. (View)

- Smith JD, Wilson S, Schneider HG. Misclassification of calcium status based on albumin-adjusted calcium studies in a tertiary hospital setting. Clin Chem. 2018;64(12):1713-1722. DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.291377. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

- Slomp J, van der Voort PH, Gerritsen RT, Berk JA, Bakker AJ. Albumin-adjusted calcium is not suitable for diagnosis of hyper- and hypocalcemia in the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1389-1393. DOI: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000063044.55669.3C. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Dickerson RN, Alexander KH, Minard G, Croce MA, Brown RO. Accuracy of methods to estimate ionized and “corrected” serum calcium concentrations in critically ill multiple trauma patients receiving specialized nutrition support. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28(3):133-141. DOI: 10.1177/0148607104028003133. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

- Byrnes MC, Hunyh K, Helmer SD, et al. A comparison of corrected serum calcium levels to ionized calcium levels among critically ill surgical patients. Am J Surg. 2005;189(3):310-314. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.11.017. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Sorva A. ‘Correction’ of serum calcium values for albumin biased in geriatric patients. Arch Geron Geri. 1992;15(1):59-69. DOI: 10.1016/0167-4943(92)90040-B. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

- Clase CM, Norman GL, Beecroft ML, Churchill DN. Albumin-corrected calcium and ionized calcium in stable haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:1841-1846. DOI: 10.1093/ndt/15.11.1841. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

- Gouri A, Dekaken A. A comparison of corrected serum calcium levels to ionized calcium levels in haemodialysis patients. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 2012;70:210-212. DOI: 10.1684/abc.2012.0693. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

- James MT, Zhang J, Lyon AW, et al. Derivation and internal validation of an equation for albumin-adjusted calcium. BMC Clin Pathol. 2008;8:12. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6890-8-12. (View)

- Antonio JM. New predictive equations for serum ionized calcium in hospitalized patients. Med Princ Pract. 2016;25:219-226. DOI: 10.1159/000443145. (View)

- Lian IA, Asberg A. Should total calcium be adjusted for albumin? A retrospective observational study of laboratory data from central Norway. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e017703. (View)

- Grzych G, Pekar JD, Durand G, Deckmyn B, Maboudou P, Lippi G. Albumin-adjusted calcium and ionized calcium for assessing calcium status in hospitalized patients. Clin Chem. 2019;65(5). DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.300392. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

- Kok MB, Tegelaers Fp, van Dam B, van Rijn JL, van Pelt J. Carbamylation of albumin is a cause for discrepancies between albumin assays. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2014;434:6-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.03.035. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Besarab A, Caro JF. Increased absolute calcium binding to albumin in hypoalbuminaemia. J Clin Pathol. 1981;34:1368-1374. DOI: 10.1136/jcp.34.12.1368. (View)

- Glendenning P. It is time to start ordering ionized calcium more frequently: preanalytical factors can be controlled and postanalytical data justify measurement. Ann Clin Biochem. 2013;50:191-193. DOI: 10.1177/0004563213482892. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:1959-1966. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

Wow! This was very informative and what seems like an important new perspective to how calcium levels should be thought about and assessed. Thanks for writing this.

Based on this evidence, I will abandon the Payne formula, and screen at low to moderate risk oncology patients with serum calcium and confirm with ionized calcium. I will order ionized calcium in high risk oncology patients.

I love it when orthodoxy is questioned and found wanting. Thank you for updating our understanding of this aspect of calcium testing.

although it is not applicable to my current practice , I found it very rational and useful and surly I will use this information in relevant discussions with my patients and other healthcare professionals.

1. Ref 15 is cited as the source for the statement “in hypoalbuminaemic states, the binding constant between albumin and calcium changes, and more calcium binds to each available gram of albumin.” Ref. 15 drew that conclusion from an inverse correlation they observed between the Calcium bound per g albumin (y axis) and albumin (x axis). Unfortunately, that correlation is statistically flawed because the measurements in the y-axis and x axis are not independent of each other (albumin appears in both). A negative correlation is tautologically inevitable and no inference can be drawn from it.

2. Great review of the weakness of the albumin correction. Correcting total calcium for both (1) the complexation of calcium by anions and (2) binding of calcium to albumin might improve the estimation of ionized calcium, but there will always be incertitude. A new method that, instead, assesses the PROBABILITY of significant hypocalcemia, based on both those corrections using only routine data–and which was, at least, internally validated in a separate cohort–was recently published by me and my co-authors. We think it could help guide the decision to measure ionized calcium. A working calculator can be downloaded from the article’s supplemental appendix if anyone wishes to try it: http://jalm.aaccjnls.org/content/early/2019/10/18/jalm.2019.029314/tab-figures-data

to Philip Goldwasser – the link you provided no longer works (it is now 2023). Is there a way you could provide a new link to your calculator?

Thanks. A working link for the calculator I referenced above is now located at qxmd:

https://qxmd.com/calculate/calculator_704/predicting-ionized-hypocalcemia-in-critical-care

Incidentally, this method underwent successful external validation twice recently:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2022.05.003

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00045632211049983