Authors

Rohit Singla PhD (biography, no disclosures), Dr. Daniel Raff MD MSc (biography and disclosures), Dr. Hester Vivier MBChB MBA (biography, no disclosures), and Dr. Andre van Wyk MBChB MBA (biography, no disclosures)

What I did before

Canadian family medicine is firmly rooted in traditional patient care principles. Physicians actively participate in face-to-face consultations, demonstrating attentive listening to patients’ concerns, and diligently documenting their medical histories and treatment plans.

On a daily basis, physicians are faced with a dilemma: if I make notes while conversing with the patient, they may feel overlooked, but doing so allows me to wrap up my day earlier, with less catch-up documentation during breaks or post-shift. It’s a constant trade-off between efficiency and building rapport. Each time one opts for the former, sacrificing a bit of that essential patient connection, it feels like yet another small slice of moral injury.

Reflect on a typical practice two decades ago: handwritten charts, often brief, with minimal patient input. This evolved with the reluctant shift to voice dictation; however, this change often led to delays and distractions, with the true essence of the patient’s concerns sometimes lost in translation. Furthermore, voice dictation, despite improving efficiency, often resulted in ‘note bloat’ — extensive notes that obscured key details and overshadowed the patient’s direct voice and concerns.

However, as time passed, a gradual “continental drift” occurred. The complexity of patient care increased, driven by advancements in medical science, a growing emphasis on incorporating patient perspectives, and increased scrutiny in documentation for regulatory and legal purposes. However, this evolution was not without its inefficiencies, impacting both patients and healthcare providers. This shift set the stage for the burnout epidemic that plagues Canadian physicians today. This reality is underscored by the alarming prevalence of burnout among Canadian physicians, with rates as high as 45.7%, and the subsequent costs to the healthcare system are staggering, estimated at $213 million.1,2 The situation was further exacerbated during the global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, where reporting and administrative obligations emerged as prominent contributors to burnout.3

One of the primary culprits contributing to this burnout crisis is the arduous documentation process entailed by traditional patient care. Physicians have diverse methods when it comes to documentation. Some craft SOAP (Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan) notes during the encounter, often disrupting active listening and patient rapport. Others opt to document post-interaction, adding to the already hefty documentation burden during breaks or at day’s end. Whether it’s typing in real-time and refining later, dictating during the visit, or documenting afterward, each physician’s approach is unique. Regardless of their approach, this labour-intensive process is not only time-consuming but also leaves healthcare providers feeling rushed, often compromising their ability to engage fully with patients.

Given the substantial patient volumes, the practice of manual note-taking exacerbates the already demanding workload. Importantly, research has identified workload as one of the principal predictors of exhaustion and cynicism among Canadian physicians.3 Despite unwavering commitment to patient care, the burdensome administrative demands associated with documentation and the imperative for efficient time management persist as ongoing challenges. Therefore, the need to streamline documentation and administrative processes has emerged as a crucial solution in addressing burnout.3

Given this scenario, the need for a solution that streamlined documentation while also enhancing patient rapport became paramount. This set the stage for our venture into conversational artificial intelligence (AI).

What changed my practice

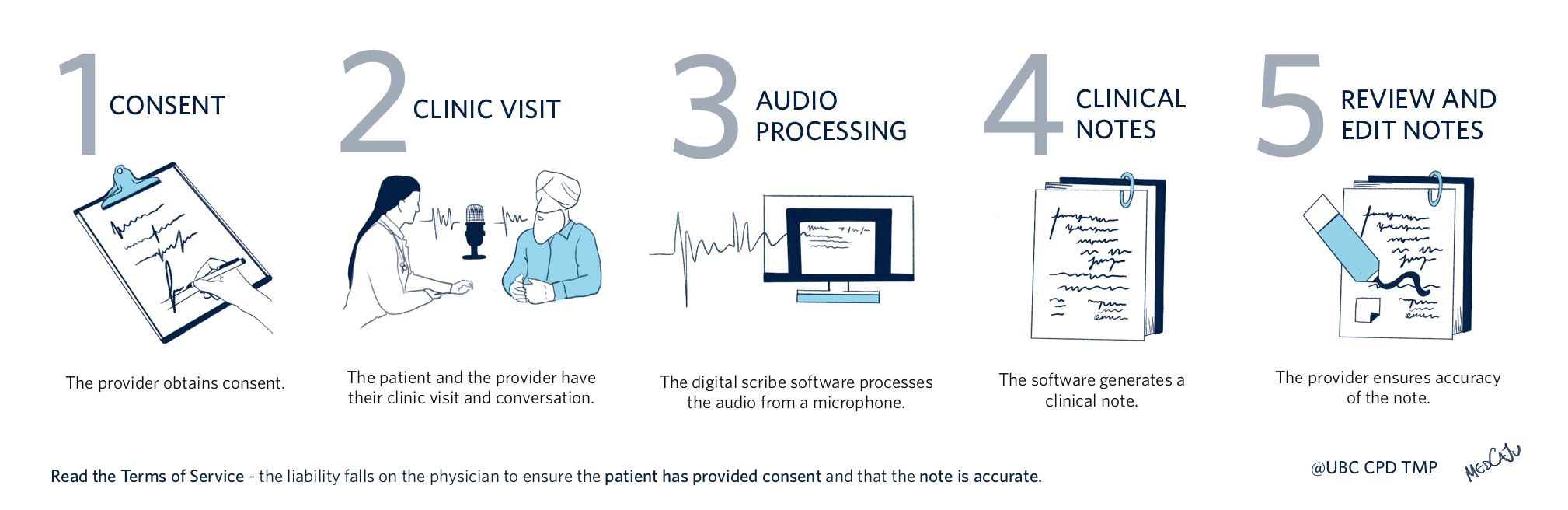

The integration of conversational AI technology, specifically a digital scribe, into daily clinical practice marked a turning point.4,5 This technology eliminates the need to type during patient consultations, seamlessly transcribing patient-physician interactions and incorporating both voices into structured SOAP format notes. No additional hardware is required beyond the computers and microphones commonly found in offices. This transformation from manual note-taking to an automated, real-time transcription process.6

Figure 1. Example clinical workflow using digital scribe technology

AI’s introduction into this dynamic amplifies active listening and fosters richer patient-physician engagement. It captures both voices holistically, preventing a solely physician-centred perspective. This improved transparency encourages physicians to be more interactive during consultations, discussing findings directly and vocalizing thoughts. For instance, members of our group find themselves more likely to have the patient on the exam table, discuss the findings of physical examinations directly with them, and articulate one’s thoughts and observations aloud. Consequently, patients are better informed, fostering increased satisfaction and a deeper clinical experience. This enhancement in patient engagement leads to increased patient satisfaction, a vital component of the modern healthcare experience.

Incorporating digital scribe technology brings marked efficiency to family medicine, especially given the high patient volumes. It not only transcribes but also assists in crafting accurate documentation. This ensures patients’ histories and care plans are meticulously recorded, enhancing care continuity. With AI managing real-time transcription and summarization, physicians can focus on prescriptions, referrals, and other tasks, streamlining workflows and reducing burnout risks. This allows doctors to give undivided attention to patients, enriching interactions and deepening rapport. As the model processes its task, the healthcare provider can work in parallel on prescriptions, referrals, and other necessary documentation. This technology even condenses extensive interactions into succinct summaries, enhancing future consultations.

However, AI isn’t infallible. Occasional misinterpretations or “hallucinations” underscore the vital role of human oversight. It’s essential to remember that while AI aids in documentation, terms of use agreements emphasize that physicians are responsible for ensuring note accuracy. This shifts the documentation responsibility from creating to thorough reviewing, much like examining a resident’s note. Additionally, refining the technology to better differentiate and annotate speakers can enhance the process further. Physicians must remain acutely aware of their ultimate liability for any inaccuracies, emphasizing the importance of meticulous oversight. Despite these challenges, integrating AI in this way signifies a promising leap forward in medical documentation.

Challenges do arise during the initial adoption phase of conversational AI, particularly regarding privacy and data security, which are pivotal under The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) in Canadian healthcare. Conversational AI tools must be and often are designed with stringent security measures, including end-to-end encryption and protocols to ensure informed patient consent, upholding PIPEDA’s privacy principles. The initial adoption demands acclimatization. Concerns regarding data security and privacy are prevalent at first, but as experience and confidence in the system grow, these concerns may gradually subside.

Providers must maintain a strong commitment to patient privacy and data security. Although these conversational AI tools streamline clinical workflows, it’s essential to recognize that when data is transmitted to cloud-based servers for processing, it may elevate the risk of privacy breaches and unauthorized data usage. Healthcare providers must diligently assess the security protocols and privacy measures of these AI solutions to ensure the confidentiality of medical information is rigorously maintained — much like they would with any software in their practice.

The College of Physicians and Surgeons Alberta’s guidelines on the use of artificial intelligence highlight this.7 Their bottom line indicates that when using AI in clinical care, physicians must obtain patient consent, ensure privacy, verify chart note quality and accuracy, provide and document appropriate follow-up advice, and exercise utmost caution due to the current speculative nature of AI’s reliability in medical charting and decision-making.

As conversational AI is woven into medical practice, beyond addressing burnout and enhancing patient care, ethical considerations, especially surrounding consent and privacy, become paramount. It’s crucial for physicians to ensure that patients are thoroughly informed about AI’s role in their healthcare and to obtain explicit consent prior to clinical visits and software usage. Given the ambiguity in terms of use agreements, there’s an urgency to integrate AI consent within electronic medical records. To strike a balance between leveraging AI for better care and safeguarding patient privacy, some physicians are taking proactive steps, such as avoiding recording identifiable patient data. This equilibrium demands consistent diligence from the healthcare sector.

What I do now

In summary, conversational AI has become a valuable tool for family physicians in Canada. It helps us provide better patient care while adapting to the changing landscape of modern medicine. It enhances physician-patient relationships and eases the burden of documentation, contributing to a more promising future for family medicine. It reduces burnout and encourages physicians to stay in the workforce. It doesn’t replace physicians but empowers them to focus on their primary mission — delivering exemplary care to their patients.

Looking forward, practitioners keen on adopting conversational AI should begin by assessing their specific needs and workflow requirements. The next step would involve a careful evaluation of available tools, such as those listed here, followed by pilot testing to ensure compatibility with existing practice operations. It is also advisable to engage in a dialogue with vendors about privacy and the possibility of customization, to ensure the chosen solution aligns closely with the unique demands of one’s clinical environment.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Canadian family medicine historically emphasized face-to-face consultations with challenges in balancing documentation and rapport.

- Increased medical complexity and stricter regulations amplified physician burnout, further intensified by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

- Documentation, with its varied methods, emerged as a major source of burnout, especially with manual note-taking.

- Conversational AI, specifically digital scribes, was introduced, transcribing interactions in real-time and enhancing active listening.

- The digital scribe system boosts efficiency, ensures accurate documentation, and reduces burnout risks.

- While AI offers benefits, it has limitations like misinterpretations, and physicians must verify note accuracy amidst data privacy concerns.

- As AI integrates into medicine, ethical issues, especially surrounding consent and privacy, are paramount.

References

- Boudreau RA, Grieco RL, Cahoon SL, Robertson RC, Wedel RJ. The pandemic from within: two surveys of physician burnout in Canada. Community Ment. Health J., 2007;25(2):71-88. (View)

- Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:254. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-254. (View)

- Leiter MP, Frank E, Matheson TJ. Demands, values, and burnout: relevance for physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(12):1224-1225.e12256. (View)

- Klann JG, Szolovits P. An intelligent listening framework for capturing encounter notes from a doctor-patient dialog. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9(Suppl 1):S3. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-9-S1-S3 (View)

- Coiera E, Kocaballi B, Halamka J, Laranjo L. The digital scribe. NPJ Digit Med. 2018; 1:61. doi:10.1038/s41746-018-0066-9. (View)

- van Buchem MM, Boosman H, Bauer MP, Kant IMJ, Cammel SA, Steyerberg EW. The digital scribe in clinical practice: a scoping review and research agenda. NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4(1):57. doi:10.1038/s41746-021-00432-5 (View)

- Artificial intelligence in generated patient record content. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta. Sep 1, 2023. Accessed Dec 12, 2023. (View)

What is College of physicians and surgeons of BC position?

If no position published can we get them working on this asap?

Thank you for the info! Is there one you have been using or recommend?

What are some recommended options for AI scribes?

I would rather we reduce/eliminate the regulatory and reimbursement pressures than add another technology to try to satisfy them.

As the majority of my patient encounters are using Language Line on speaker phone translating 5+ different languages a day this would be crazy to try. I would love to see how AI makes out with Kinyrwanda! I would be happy to have an EMR that functions better than a glorified word processor. I am very unhappy with Practice Solutions which was once upon a time the CMA flagship EMR

Hi All,

There are many potential vendors. We would recommend searching online for an AI medical scribe. Example Canadian vendors:

AutoScribe by Mutuo . com (Toronto, ON, Canada)

Scribeberry . com (Toronto, ON, Canada)

Tali AI . ai (Toronto, ON, Canada)

Disclaimer: We are not recommending any specific vendor and we have no affiliation with these companies.

With the vendors who keeps a record (no matter how briefly – some states 1 week), I am quite concerned re data safety, and with all vendors, I don’t at all trust that they don’t do some sort of Data Mining. The vendor will gain knowledge of your practice even if your patients were anonymized – YOU are not (anonymized). They will be able to generate a profile on your medical practice on such as: how long is your avg visit, % of time you talk vs pt talk, things like top 10 most common diagnoses, and even patterns of your management steps. On a superficial level, they collect and sell this aggregate data about you (to marketers) – not at all unlikely, unless protected explicitly by contract or by law / regulations. On a deeper level, the AI learns how you as a physicians manage various types of complaints, and well, perhaps replicate or replace you (us)….?

What are the most reliable AI vendors?

Thank you for the excellent article! Would you be willing to share the consent form you use? I’ve been using Scibeberry and drafted my own patient consent form after being unable to find one (and there is no position statement or guidance from CPSBC yet)

I have been using AI to summarize patent interactions in the office. Estimate 10% are really accurate, 30% are useless, and the rest fall somewhere in between. My total time spent on paperwork has increased. Plus we have to get consent from everybody. I find they are most useful with a single clearly defined problem (like sore throat), and with very long histories, such as mental health. However the notes can be lengthy and require a lot of editing.

Please note that CPSBC has published new interim guidance on artificial intelligence, view at https://www.cpsbc.ca/news/publications/college-connector/2024-V12-03/03.