By Trana Hussaini Pharm D (biography, no disclosures) and Eric M. Yoshida MD FRCPC (biography and disclosures)

What I did before

The World Health Organization has set an ambitious goal of eliminating hepatitis C by 2030 and this is by no means an easy task (1). Worldwide, approximately 71 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis C (2). Although asymptomatic during the early stages, chronic infection with hepatitis C can lead to progressive hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma with a global liver-related mortality rate of 350,000 people per year (3). In Canada, it is estimated that up to 246,000 Canadians are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) with a significant majority (44-70%) being unaware of their infection (4,5). In British Columbia, approximately 73,000 people harbour hepatitis C infection (6).

The road to HCV therapy has been long and painful. The previous standard of care combination therapy involved a prolonged course of parenteral (pegylated interferon) and oral (ribavirin) medications administered for 6 to 12 months with intolerable side effects and marginal treatment success rates (7). In 2013, the introduction of direct acting antiviral agents (DAAs) revolutionized hepatitis C therapy, offering safe and highly efficacious treatment regimens with success rates exceeding 95% (8, 9).

What changed my practice

For the first time, since the identification of hepatitis C virus, the goal of HCV elimination is a tangible and achievable target mainly due to the availability of highly efficacious and well tolerated DAA regimens. Unlike interferon and ribavirin, DAAs act by inhibiting specific targets during viral replication cycle; hence, they effectively shut down viral replication (10). Broadly categorized as NS3/4A protease Inhibitors (Grazoprevir, Glecaprevir, Voxilaprevir), NS5A replication complex inhibitors (Ledipasvir,Elbasvir, Velpatasvir, Pibrentasvir), and NS5B polymerase inhibitors (Sofosbuvir), these agents are often combined and co-formulated into a single tablet regimen administered once daily for 8 to 12 weeks (11). All combinations are well tolerated with headache, nausea and insomnia being the most common reported side effects.

Protease inhibitors can rarely cause hepatic biochemical abnormalities and are contra-indicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh Class B or C) (12). Sofosbuvir is renally eliminated, thus its use is not recommended in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (eGFR < 30 ml/min) (12). Clinically significant drug-drug interactions exist when DAA regimens are combined with commonly prescribed medications such as proton pump inhibitors and statins; therefore, clinicians are encouraged to consult appropriate drug interaction references prior to treatment initiation (13). The most commonly utilized DAA regimens are summarized in Table 1. All regimens are covered by BC PharmaCare under the Special Authority Program (14).

| DAA Regimen | Genotype Coverage | Daily dosage | Duration | Safety in advanced CKD | Safety in Decompensated Cirrhosis |

| Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir

(LDV/SOF) 15 |

1,4,5,6, | One tablet (90/400 mg) once daily

|

8-12 weeks | Not recommended if GFR <30 ml/min | Safe |

| Elbasvir/Grazoprevir

(EBR/GZR) 16 |

1,4 | Once tablet (50/100 mg) once daily

|

12-16 weeks | Safe | Contra-indicated if Child-Pugh Class B, C |

| Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir

(SOF/VEL) 17 |

1,2,3,4,5,6

(pan-genotypic) |

One tablet (400/100 mg) once daily

|

12 weeks | Not recommended if GFR <30 ml/min | Safe |

| Glecaprevir/Pebrintasvir

(GLE/PIB) 18 |

1,2,3,4,5,6

(pan-genotypic) |

Three tablets (300/120 mg) once daily with food

|

8-16 weeks | Safe | Contra-indicated if Child-Pugh Class B, C |

| Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir

(SOF/VEL/VOX) 19 |

1,2,3,4,5,6

(pan-genotypic) |

One tablet (400/100/100 mg) once daily with food

|

12 weeks | Not recommended if GFR <30 ml/min | Contra-indicated if Child-Pugh Class B, C |

What I do now

To be on track with HCV elimination targets, a country must diagnose 90% of its infected population and treat 80% without any restrictions on treatment based on disease severity (1). Therefore, efforts should focus on scaling up HCV screening, removing treatment barriers, and initiating prompt treatment in individuals who are chronically infected.

Scale up screening:

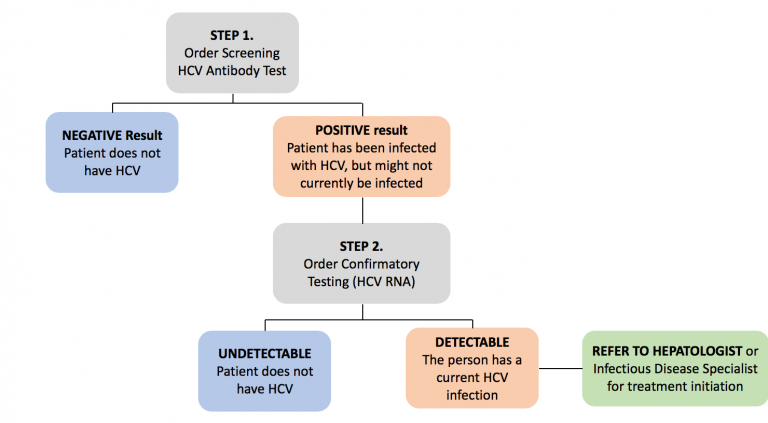

Given that a significant proportion of Canadians who are chronically infected with HCV are undiagnosed, HCV screening is the first step towards identification and treatment of HCV (4,5). In the primary care setting, all patients who are at increased risk of HCV infection should be screened (20, 21). High risk populations include those with history of current or past intravenous drug use, HIV infection, or incarceration, those born between the years of 1945 and 1975, or individuals born in areas of high HCV prevalence (20, 21). The diagnostic test of choice for initial screening is anti-HCV antibody testing. If positive, a HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) should be ordered to confirm infection (20, 21).

Scale up treatment:

Structural barriers to HCV treatment should be eliminated to facilitate access to therapy for all infected individuals. The significant cost associated with DAAs was a major prohibiting factor in the past leading to restriction of treatment to patients with advanced liver disease only. Fortunately, the requirements for disease severity have been removed and currently almost all patients infected with hepatitis C are eligible to receive treatment (14). Individuals who test positive for HCV RNA PCR should be referred to a gastroenterologist or an infectious diseases specialist with expertise in treating hepatitis C (Figure 1). Likely in the near future, the provider restrictions will be lifted with expansion of HCV treatment providers to non-specialists and primary care physicians. This will allow for universal, timely and appropriate care for all infected individuals.

In summary:

Screen patients who are at high risk for HCV infection. Patients with positive anti-HCV antibody should be tested with a confirmatory HCV RNA PCR. All patients with chronic HCV infection should be considered candidates for antiviral therapy and should be referred to a HCV care provider for treatment initiation.

Patient Info:

- Patient information sheet on hepatitis C. Canadian Liver Foundation. https://www.liver.ca/patients-caregivers/liver-diseases/hepatitis-c/ (accessed Oct 20, 2019)

Resources:

- 2018 HCV Guidelines. Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. https://hepatology.ca/publications/guidelines/2018-hcv-guidelines/ (accessed Oct 20, 2019)

- Hep Drug Interactions. University of Liverpool. 2019. https://www.hep-druginteractions.org/checker (accessed Oct 20, 2019)

- The management of chronic hepatitis C: 2018 guideline update from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. CMAJ 2018 June 4;190:E67787. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5988519/pdf/190e677.pdf (accessed Oct 20, 2019) Ref 20

Figure 1. Hepatitis C screening, testing and treatment algorithm. Modified from Blueprint to inform hepatitis C elimination efforts in Canada (21)

References

- World Health Organization. Combating hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030. Published May 2016. Accessed August 14, 2019. (View)

- Hepatitis C Fact Sheet. World Health Organization. Updated July 9, 2019. Accessed August 12, 2019. (View)

- Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A, et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):77-87. DOI: 10.1005/hep.27259. (View)

- Trubnikov M, Yan P, Archibald C. Estimated prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Canada, 2011. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2014;40(19):429-436. DOI: 10.14745/ccdr.v40a19a02. (View)

- Rotermann M, Langlois K, Andonov A, Trubnikov M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections: results from the 2007 to 2009 and 2009 to 2011 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Rep. 2013;24(11):3-13. (View)

- Janjua NZ, Kuo M, Yu A, et al. The population level cascade of care for hepatitis C in British Columbia, Canada: The BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC). EBioMedicine. 2016;12:189-195. DOI: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.035. (View)

- Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358(9286):958-965. DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Lim TR, Tan BH, Mutimer DJ. Evolution and emergence of a new era of antiviral treatment for chronic hepatitis C infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;43(1):17-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.09.008. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Falade-Nwulia O, Suarez-Cuervo C, Nelson DR, Fried MW, Segal JB, Sulkowski MS. Oral direct-acting agent therapy for hepatitis C virus infection. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):637-648. DOI: 10.7326/m16-2575. (View)

- Alazard-Dany N, Denolly S, Boson B, Cosset FL. Overview of HCV life cycle with a special focus on current and possible future antiviral targets. Viruses. 2019;11(1):30. DOI: 10.3390/v11010030. (View)

- Spengler U. Direct antiviral agents (DAAs) – A new age in the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;183:118-126. DOI: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.10.009. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Banerjee D, Reddy KR. Review article: safety and tolerability of direct-acting anti-viral agents in the new era of hepatitis C therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(6):674–696. DOI: 10.1111/apt.13514. (View)

- Néant N, Solas C. Drug-drug interactions potential of direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;13:30. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.10.014. (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Special Authority Request Forms. BC PharmaCare. Updated 2019. Accessed August 12, 2019. (View)

- Gilead Sciences. HARVONI Highlights of Prescribing Information. Updated August 2019. Accessed August 12, 2019. (View)

- Merck. ZEPTATIER Highlights of Prescribing Information. June 2018. Updated June 2018. Accessed August 12, 2019. (View)

- Gilead Sciences. EPCLUSA Highlights of Prescribing Information. Updated November 2017. Accessed August 12, 2019. (View)

- AbbVie. MAVYRET Highlights of Prescribing Information. Updated December 2017. Accessed August 12, 2019. (View)

- Gilead Sciences. VOSEVI Highlights of Prescribing Information. Updated November 2017. Accessed August 12, 2019. (View)

- Shah H, Bilodeau M, Burak KW, et al. The management of chronic hepatitis C: 2018 guideline update from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. CMAJ. 2018;190(22):E677-687. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.170453. (View)

- The Canadian Network on Hepatitis C Blueprint Writing Committee and Working Groups. Blueprint to inform hepatitis C elimination efforts in Canada. Montreal, QC. Accessed Oct 20, 2019. (View)

Clear concise summary of status of HCV. Thank you

We already screen for HepC and HIV when pts arrive in our ER, but after reading this article, I wonder if we can “up the ante” on follow-ups. I think we just assume someone looks at the results and takes care of it.

The clients I attend are youth, this treatment appears to be focused on the client being mature. What algorithm would address a younger population i.e. youth 12-18?

‘To be on track with HCV elimination targets, a country must diagnose 90% of its infected population and treat 80% without any restrictions on treatment based on disease severity.’ As a primary care provider and addiction medicine physician, I see an unmet need in this area. I am inspired to be good enough to diagnose and treat Hepatitis C!

As a family doc who treats hep c, this is insulting! To have a specialist imply specialist should treat hep c is old fashioned and will NOT result in 2030 targets.

We were invited to provide an article that reflected how medical advancements affected our practice at the Vancouver General Hospital. The article was reviewed and we were invited to make revisions based on the reviewers’ comments. The version that is posted incorporated the comments of the reviewers.

In regards to hepatitis C therapy with direct acting antiviral agents, Pharamcare restricts their approval of these drugs to gastroenterologists, infectious disease specialists and those with experience in treating hepatitis C. We stated in our article that in the future, we felt that this restriction could be removed.

In regards to who treats patients with chronic hepatitis C, under the current system, specialists can only see patients if they are referred whereas family physicians have the choice of referring patients to specialists or deciding to treat these patients on their own. Some family physicians may have undertaken extra training in this area and may feel very comfortable prescribing antiviral therapy and monitoring these patients throughout treatment (and Pharmcare would consider them as “specialists”). It would not be inappropriate for those family physicians to exclusively manage these patients.

Many family physicians, however, may not feel as comfortable managing these patients alone and it is certainly not inappropriate for those family physicians to refer them onto specialists. It was not our intention to enter into a discussion about medical politics but rather to provide education about the new developments in hepatitis and the stated goal of the World Health Organization to eradicate hepatitis C by 2030.

In response to another question, yes, the direct acting antiviral agents are safe and appropriate for youths but pregnancy must be avoided during treatment.

These DAAs have been such a game changer!

I’ve caught a few previously unknown HCV infections in patients screened for risk factors in ER and one in a patient screened based on age alone (based on the CASL guideline, and in contravention of the CTFPHC guideline). The screening recommendation above was a sneaky blend of the two guidelines, as the CTFPHC guideline actually DOESN’T include age/birth year as a high risk criterion – CASL is the one that recommends screening for those born between 1945-1975.

Advance notice: elbasvir-grazoprevir (Zepatier®) delisting

https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/health-drug-coverage/pharmacare/newsletters/news22-006.pdf

PharmaCare will delist elbasvir-grazoprevir (Zepatier®) 50 mg/100 mg tablet on August 1, 2022, because of the manufacturer’s decision to remove it from market.

In April 2022, Merck Canada Inc. announced it was ceasing the sale of Zepatier, after evaluating clinical use and the availability of alternative therapies. The decision was not related to any quality or safety issues, the company stated.

Zepatier was listed as a limited coverage drug on March 1, 2017, as part of a coverage expansion of direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C (CHC).

Zepatier can still be sold—and will still be covered by PharmaCare—until July 31, 2022, by which the manufacturer estimates remaining inventory will be depleted.

The Adults with Chronic Hepatitis C information sheet (PDF, 129KB) will be updated on August 1, to reflect Zepatier’s new non-benefit status.