Dr. Joanna Cheek (biography, no disclosures)

What I did before

Like many physicians, I chose medicine as a career that allowed me to practice — and strongly reinforced — my underlying values of service, stoicism, and excellence.

When COVID-19 was announced a pandemic, I began leading a team of physicians to help develop a mental health response for frontline workers in this crisis. Our team left the gates in a mad dash. Despite the majority of the team being frontline workers themselves, facing redeployment into uncertain roles and having children at home with no childcare, we raced ahead creating strategies to support our colleagues’ mental health, while dismissing our own.

I ignored that I was scared each day as my hospitalist husband went to work in the ER, that my children were struggling at home and needed a present parent, that I worried how I was going to care for my vulnerable patients adequately from a screen. I felt numb to every emotion except frustration, spiraling into rage whenever an obstacle interfered with my productivity. My colleagues pointed out their concern with my pattern of sending work emails earlier and earlier every day, with many at 3 am, as I couldn’t find enough time in the day to do it all. When checking in with my team, I soon realized I was not the only one sprinting towards burnout.

What changed my practice

When researching the different models of psychological first aid, our team found a webinar by Dr. Patricia Watson, from the US National Centre for PTSD [1]. She outlined how our shared values of selflessness, pursuing excellence and stoicism seen in health care workers act as a double-edge sword.

While selflessness allows us to serve others, we often don’t seek help when our own health is at risk. While we may be able to endure hardships without complaints, we may not be aware of our own early warning signs of distress. While we strive to perform perfectly in high stakes environments, we can feel shame when we can’t do it all, make mistakes, or need to slow down to take care of ourselves.

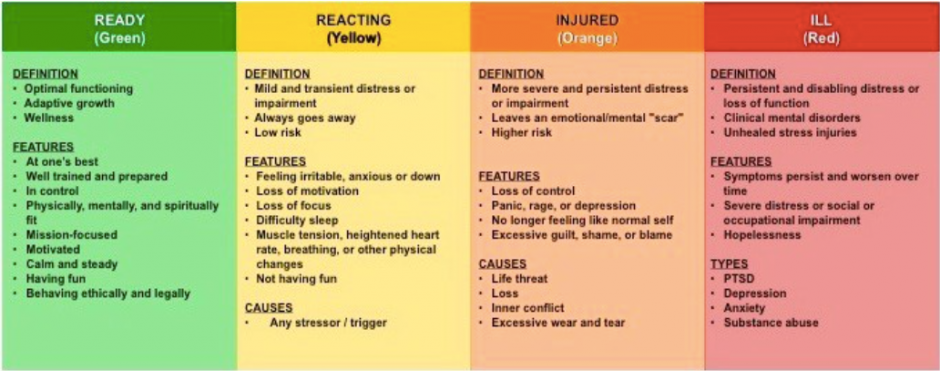

Dr. Watson illustrates how to translate the military’s Stress Continuum model to help health care workers recognize the spectrum of distress in both our peers and ourselves. Using the colors of a traffic light to guide our response, we can learn to pay attention to the signs of when we’re okay to keep working (green), and when we need to slow down (yellow or orange) or pause (red), so we can pace ourselves for the marathon ahead. When one of us is moving out of the green zone, we can help each other by normalizing this as a common response to this stressful time, support each other, and transfer the workload back and forth as necessary.

Figure 1: The Stress Continuum Model

Nash, W. P. (2011). US Marine Corps and Navy combat and operational stress continuum model: A tool for leaders. Combat and operational behavioral health, 107-119.

What I do now

- We actively encourage and model psychological safety in our teams by sharing our own vulnerability in the here and now (not simply telling stories of past struggles while comfortably concealing vulnerability in the present).

- We acknowledge that most people are unlikely to spontaneously ask for help. We try to normalize distress by including it as a regular part of team meetings. We start each team meeting with a check-in that includes how we are doing emotionally and what color we are on the Stress Continuum.

- We introduce the concept of “passing the baton”, so that once we identify a team member to be moving to the right of the continuum, we then transfer their workload to other members without judgment.

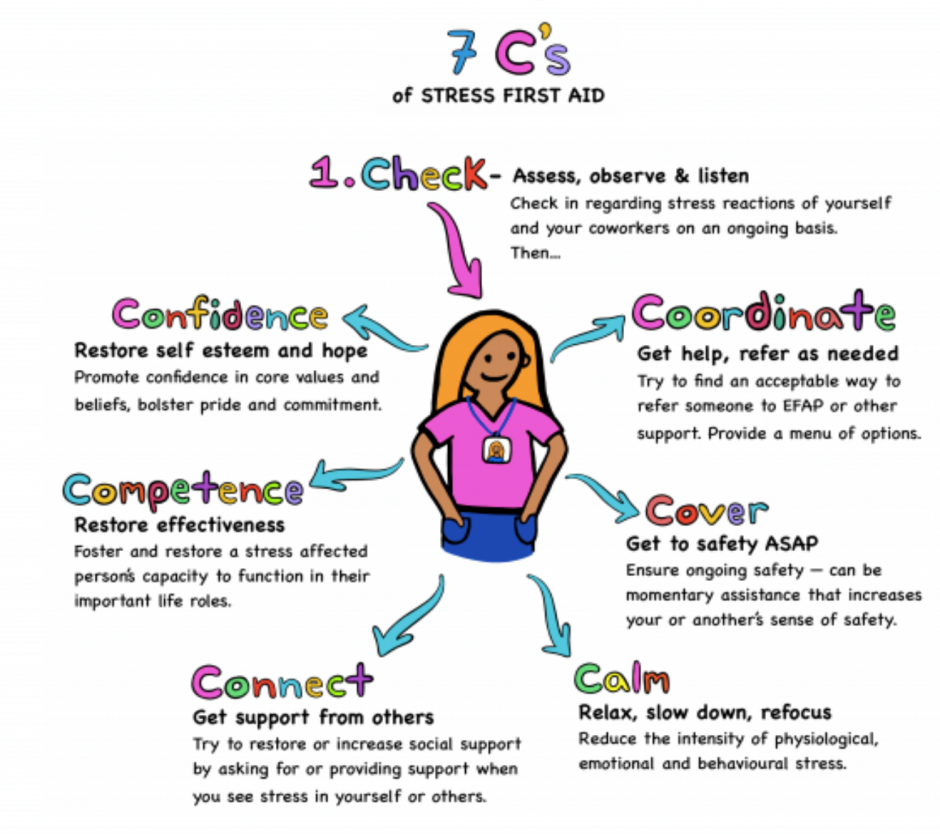

- We use the Stress First Aid model, borrowed from the military, to support our team members in moving back towards the left of the continuum through the 7 C’s (below) [2]. This model was developed to put into practice the evidence-based tenants of resiliency:

- Check-in:

- Observe and listen for signs of distress (using the Stress Continuum Model for reference).

- Approach with non-intrusive and nonjudgmental curiosity with the question, “What do you/I need right now?” and “How can I help?”

- Coordinate:

- Get help and link to supports as needed.

- The BC Physician Health Program offers a 24/7 support line linking physicians to mental health services at 1-800-663-6729

- The Canadian Psychological Association offers a list of volunteer psychologists for frontline workers at https://cpa.ca/corona-virus/psychservices/#BritishColumbia

- Get help and link to supports as needed.

- Cover:

- Improve one’s sense of safety:

- Physical safety: e.g. provide accurate information, appropriate PPE and policies, quiet rooms away from the chaos, support sick leave

- Psychological safety: create an environment where the four levels of psychological safety are supported[3]

- Inclusion safety: inclusion to belong on team and protect everyone’s safety

- Learner safety: permission to learn and make mistakes without criticism

- Contributor safety: permission to contribute to team with autonomy

- Challenger safety: permission to challenge status quo (e.g. can speak up if they feel unsafe)

- Improve one’s sense of safety:

- Calm:

- Help bring down hyper-arousal (e.g. increase self-care like exercise, healthy distraction and time off; practice calming techniques—breathing exercises, grounding practices such as mindful hand washing, 54321—notice 5 things you see, 4 things you feel, 3 things you hear, 2 things you smell, 1 thing you taste; self-compassion).

- Connect:

- Encourage and prioritize social support from others.

- When supporting peers, remember compassion requires boundaries: allow yourself to assert what is okay and not okay for you to sustain support (e.g. turning off your phone in the evenings to be with family uninterrupted)

- The Physician Health Program is offering free virtual drop-in COVID-19 physician peer support sessions https://www.doctorsofbc.ca/news/covid-19-physician-peer-support-sessions.

- Various groups have popped up on social media to provide peer support such as the COVID-19 Women Physicians Emotional Well-being Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/groups/235295047624227/.

- Competence:

- Restore a sense of effectiveness in many areas of life (work, home, health).

- Identify skill gaps and seeking mentoring:

- The UBC Rural Coaching and Mentoring Program (CAMP) provides peer support for a variety of areas, including personal wellness, COVID-19, and virtual care at https://ubccpd.ca/camp

- When COVID-19 pushes us into unfamiliar territory, also re-engage in familiar roles and tasks to re-establish competence

- Confidence:

- Normalize distress and concentrate on strengths; reconnect to core values; honor and make meaning of losses; foster hope.

- g. How can we practice our values during this crisis?

- Normalize distress and concentrate on strengths; reconnect to core values; honor and make meaning of losses; foster hope.

- Check-in:

Image created by UBC Medical Student Caroline Dance.

This model is not linear — we don’t need to work through all the steps. The key is to ask, “What is needed right now?” For example, I observe that my colleague is anxious. Perhaps I can ask how they could feel more safe, calm, and competent to manage the distress.

It’s not easy to train in new skills to support our mental health when the race has already begun. We are all going to cycle out of the green zone many times, regardless of our practice of self-care. We need each other right now to provide peer support to help each of us notice when we’re moving to the right of the stress continuum and pause or pace ourselves so we can complete this marathon together.

References

- Watson, P (2020). Caring for Yourself and Others in the COVID-19 Pandemic. (View) Accessed July 30, 2020.

- VA National Center for PTSD (2018). Stress First Aid Self-care/Organizational Support Model. (View) Accessed July 30, 2020.

- Clark, T (2020). The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety. Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland. (Find in library) Accessed July 30, 2020.

Wow! What an amazing article. I really appreciate the summary pictogram (way to go Caroline Dance!) and the use of the military stress continuum. Will try using that with my team and recognizing when I’m drifting to the yellow so that I can offload to stay in the green.

This is very helpful. I already do most of this, and having it written out clearly and succinctly will help me share it with my team and model more effectively. We all need to keep this on the radar, and this is a very helpful reminder.

I think we need a peer-to-peer mentorship program for all interested physicians,not just rural ones. This time of crisis and acute change in health care systems ,with the emerging possibilty of talking about our vulnerabiilty makes this the perfect moment to get one started. Anyone interested?

Thanks, this is a great summary and I definitely found myself working through this and on these continuums. This puts into words what has been running through my head. Thank you for the helpful suggestions to focus on what to do to help as well.

Hi Julie Martz–I love the idea of a peer-to-peer mentorship program. Lets chat–joannacheek@gmail.com

I appreciate this article. But am also conscious of how primary care is currently organized in BC, where there are no real teams at which to have such conversation and no way to share work that would not reduce income. I suspect that we will see even more people leaving community-based, longitudinal primary care environments and more family doctors choosing to work in specialized areas where they have the support of a real team who can provide the supports and processes described.

I like this idea a lot and I am interested in having a framework to use for checking in and naming the ways stress affects our functioning. Usually when I seek support my physician colleagues are happy to provide it but very reluctant to receive it – an interesting commentary on the culture.

But what to do when “green” sounds totally unrealistic… does anyone in medicine actually ever get to feel that way? I have internalized the belief that if I’m in “green” I’m not pulling my weight in the healthcare system. I would feel guilty for my paycheque if I was having “fun”.

Like a previous article on “presenteeism” in physician culture, this all makes sense, yet feels completely unrealistic in my remote primary care setting, where the luxury of setting boundaries on my time is simply an impossibility. The impacts of forced absenteeism during the pandemic, for coughs and sniffles and possible covid contacts, have only proven how disruptive it is to the small and fragile team, and to the patients, to reduce one’s workload.

The silver lining? At least, like in the military, the experience of shared adversity binds me deeply to my colleagues.