Author

Dr. Arman Abdalkhani (biography and disclosures). Disclosure: UBC SIF Grant for Surgical Education. Mitigating potential bias: recommendations are consistent with current practice patterns.

What frequently asked questions/gaps I have noticed

Otolaryngologists receive many referrals for what is classified as Eustachian Tube Dysfunction, aural fullness, and subjective hearing loss. Practitioners frequently encounter ear fullness or subjective hearing loss, in the face of an otherwise normal exam. It may lead practitioners to “read into” their physical exam with abnormal tympanic membrane (TM) findings. The tympanic membrane is very difficult to examine, and findings of erythema, edema, otitis, etc. can be ascribed to a normal TM or a TM with chronic changes that do not accurately reflect the underlying cause of the patient’s ear symptoms. In my experience, many of these patients are young and have no other chronic medical conditions that would account for their ear symptoms.

Data that answers these questions/gaps

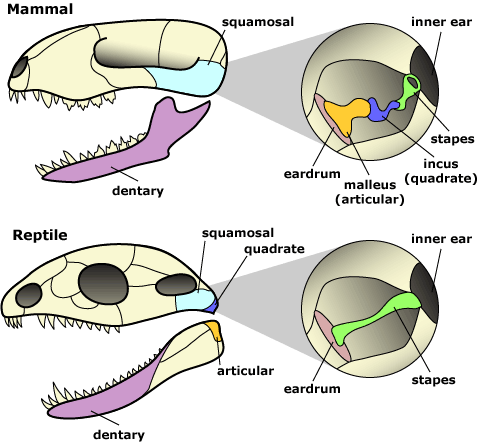

The interplay between orofacial dysfunction and ear symptoms has its origins in our evolutionary development. Roughly 170 million years ago our reptilian ancestors and mammalian ancestors displayed distinctive skeletal changes: two reptilian jawbones were adapted for hearing with their muscular derivatives (fig. 1). This resulted in the unique chewing motion of the mammalian temporal mandibular joint, and the evolutionary advantage of hearing higher pitched sounds with the new 3-boned ossicular framework.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the three mammalian ossicles. With permission © UC Museum of Paleontology Understanding Evolution, www.understandingevolution.org.

This foray into evolution helps the patient understand the intimate relationship of these structures. It also helps the clinician understand the embryologic first branchial arch derivatives responsible for the malleus and incus, as well as the muscles of mastication. The trigeminal nerve is therefore responsible for the motor innervations to these structures. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that overlap of innervation and muscular contributions to this area makes it a particularly confusing clinical entity to deal with.

TMD (Temporal Mandibular Disorders) is a collective term for different types of conditions and symptoms of the jaw and surrounding structures. It is not a diagnosis but includes various diagnoses with different backgrounds and pathophysiology. The symptoms of orofacial pain and dysfunction are quite common, being reported by about 10% of the population, with the highest frequency among women 20–60 years of age (Lovgren et al., 2016).

Many studies have found associated aural symptoms in TMD patients. These include 43–96% of patients with TMD reported ear fullness and 32–77% reported otalgia (Porto De Toledo et al., 2017). In another study when patients were referred to a specialist clinic due to TMD symptoms with coincident ear symptoms and examined by an otolaryngologist, none had an ear pathology, except for a few patients with impaired hearing (Mejersjö & Näslund, 2016).

What I recommend (practice tip)

It is trite to say, but proper diagnosis with a full history and physical is paramount. If the patient has cyclical ear fullness/pain without hearing loss and without ear discharge and does not have ear pressure changes on airplane flights, the clinician’s suspicion for TMD should be heightened. In addition, if the pain and fullness do not correspond with recent URTI or aero-allergen flare, and is worse after meals or first when awakening (likely from a night of unknown bruxism), the likelihood of inherent ear pathology decreases. A heightened suspicion for TMD would also be consistent with the following exam findings: the TM appears clear without effusion, the Weber and Rhinne tuning fork tests are normal, the ipsilateral TM joint is tender to palpation upon opening/closing, an ipsilateral click is heard or felt at the TM joint on opening/closing, or signs of dental wear consistent with bruxism (fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Note the changes especially apparent on the lower teeth with flattening and worn-away enamel. With permission © Sunrise Village Dental Centre Copyright 2021.

An audiogram from a local provider can be obtained to verify normal hearing although a tuning fork test and subjectively normal hearing would make a confirmatory audiogram less urgent.

After the clinician has placed TMD high on the differential list the following conservative measure can be attempted for 3-6 months. If these therapies are not helpful, an ENT consultation can be requested for further assistance in the diagnosis.

- Occlusal splint and referral to TMD specialist (DDS). A bruxism guard vs TMJ splint are different interventions and a referral to TMD dental specialist is typically recommended. The patient’s own dentist may feel comfortable making a bruxing guard, but this may not address the underlying TMD, whereas a TMJ splint made by a TMD specialist provides more vertical support for the jaw and puts masticator muscles in a neutral position.

- Masticator massage — three weekly 30-minute sessions of massage of the muscles of mastication for at least four consecutive weeks (Fidelis de Paula Gomes, 2015). Massage therapy is best performed by an RMT who has undergone training involving sliding and kneading maneuvers on the masseter and temporal muscles. The patient can inquire from their preferred RMT if they have experience in this regard. After the initial visits, patients can often self-administer the massage.

- NSAIDS for symptomatic relief.

- Avoid gum chewing and soft food diet as needed for pain symptoms.

- Warm compresses can help relieve local muscle tension over the masseter muscle and temporalis muscle on the ipsilateral side.

- Bo Tox injections are available for more severe cases. There are several TMD specialists and Otolaryngologists who will provide 25–30 units of Bo Tox to the masseter and temporalis muscles to help relieve symptoms.

Resources

- I highly recommended the summary at American Family Physician: Gauer RL, Semidey MJ. Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Mar 15;91(6):378-86. PMID: 25822556. (View)

- Patient Handout: Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals NHS Trust. Temporomandibular Disorders, Information for patients. (View)

Reference

- Gomes CAFP, El-Hage Y, Amaral AP, et al. Effects of Massage Therapy and Occlusal Splint Usage on Quality of Life and Pain in Individuals with Sleep Bruxism: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Jpn Phys Ther Assoc. 2015;18(1):1-6. doi: 10.1298/jjpta.Vol18_001. (View)

- Lovgren A, Haggman-Henrikson B, Visscher CM, Lobbezoo F. Temporomandibular pain and jaw dysfunction at different ages covering the lifespan – A population based study. Eur J Pain. 2016;20(4):532-540. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

- Mejersjö C, Näslund I. Aural symptoms in patients referred for temporomandibular pain/dysfunction. Swed Dent J. 2016;40(1):13. (Request with CPSBC or view UBC)

- Porto De Toledo I, Stefani FM, Porporatti AL, et al. Prevalence of otologic signs and symptoms in adult patients with temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical oral investigations. 2017;21:597-605. DOI: 10.1007/s00784-016-1926-9. (Request with CPSBC or view with UBC)

Good succinct article on a poorly understood relationship.

good article, informative and helpful

Thank you for this article. A few observations:

1.There are no “TMD” or “TMJ” specialists. In Canada, the specialty is Oral Medicine. In the USA, the specialty is Orofacial Pain.

2. Dental orthotic efficacy? Zhang SH et al. Acta Odontol Scand 2020; Al-Moraissi EA et al. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020; Zhang L et al. Ann Palliat Med 2021. Note: TMD/TMJ “specific” orthotic design inconsequential.

3. Botox efficacy? Delcanho R et al. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2022. Note: questionable.

Is Botox recommended bilaterally to ensure equal strength of bite when tmj pain is unilateral, or unilateral only? Thank you

Excellent. Really. Thank-you.

This reinforces the famous biology comment of Dobzhansky’s that nothing can be understood unless through the lens of evolution. It also reinforces the psychological principle that “seeing is not believing, believing is seeing” but I doubt patients will stop getting conned into all sorts of expensive,useless, and potentially dangerous TMJ quackery, the complications of which the taxpayers will continue to pay for.