By Dr. Matthew Clifford-Rashotte (biography, no disclosures) and Dr. Natasha Press (biography and disclosures)

What frequently asked questions I have noticed

A 25-year-old man presents to your clinic for routine sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing. He has no symptoms nor known contacts with STIs. He has a history of previously treated syphilis, but is otherwise well.

His syphilis serology results are as follows: Syphilis EIA positive, RPR negative, TP-PA positive.

How should these results be interpreted?

We frequently encounter questions about the interpretation of syphilis serology and about the appropriate treatment of various clinical stages of syphilis.

Data that answers these questions/gaps

Syphilis rates have been rising in British Columbia, and across Canada, since the early 2000s1. In order to control this epidemic, clinicians must test at-risk patients, and interpret tests correctly in order to provide appropriate treatment. Interpretation of syphilis serology can be challenging, and misinterpretation may result in undertreatment or overtreatment, depending on the context.

When to test

Rising syphilis rates call for an urgent scale-up in testing. Potentially symptomatic patients (genital ulcer, rash involving palms and soles, or unexplained cranial nerve abnormalities, meningitis, etc.) should all be tested. Testing should also be performed in key groups of asymptomatic individuals:

- Pregnant women (both during the first trimester, and again at time of delivery – see below)

- Sexually active gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM)

- People with multiple sexual partners, those engaging in sex work, and those with symptoms of, or being tested for, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- People living with HIV

In the first half of 2019, two cases of congenital syphilis were reported in British Columbia, the first cases since 2013. As a result, the BCCDC has released an interim guideline2 recommending testing during two timepoints in pregnancy – during the first trimester or at the first prenatal visit, and again at the time of admission for delivery, or at 35 weeks for those who will not be giving birth in a hospital.

Interpreting test results

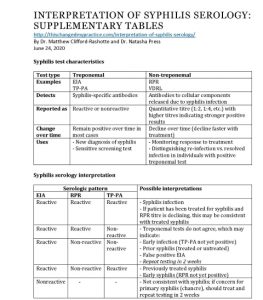

Serologic tests for syphilis are divided into two categories1:

- Treponemal tests, like syphilis EIA and TPPA, detect syphilis-specific antibodies. Once an individual has been infected with syphilis, these tests will usually remain positive for life, and thus they are no longer useful in distinguishing new versus prior infection.

- Non-treponemal tests, like RPR and VDRL, detect antibodies to cellular components released during tissue damage caused by syphilis. As a result, they are less specific, and can be elevated due to other conditions, including autoimmune diseases or acute febrile illnesses. These tests are reported as titres, which are used to monitor response to treatment or to ascertain reinfection in people with positive treponemal tests. With or without treatment, non-treponemal test titres will decline over time.

Historical testing algorithms for syphilis employed a two-stage approach, first by screening with a non-treponemal test, then performing a treponemal test for confirmation. Contemporary “reverse” screening algorithms, employed in British Columbia and in many other jurisdictions, screen first with an EIA (treponemal test), then perform an RPR (non-treponemal test) if positive, usually followed by an additional treponemal test (e.g. TP-PA) for further confirmation. Because non-treponemal tests take longer to turn positive in early infection and decline over time even in untreated individuals, screening with treponemal tests first is a more sensitive approach.

Here are some examples of common serologic patterns and their interpretation:

- EIA reactive, RPR reactive, TP-PA reactive

This is consistent with syphilis infection. If the patient has previously received treatment and the RPR titre is declining, it may be consistent with treated syphilis. - EIA reactive, RPR reactive, TP-PA non-reactive, OR

EIA reactive, RPR non-reactive, TP-PA non-reactive

The treponemal tests do not agree. This may be due to early infection where TP-PA has not yet developed, prior syphilis (treated or untreated), or potentially a false positive EIA. This patient should be re-tested in 2 weeks. - EIA reactive, RPR non-reactive, TP-PA reactive

Remember that treponemal tests will generally stay positive for life, so if the patient has previously been treated for syphilis, this is the expected serologic result. If the patient has never been treated, this could also be consistent with late latent syphilis, as RPR titres decline over time, with or without treatment. Confirming treatment history in this situation is essential to avoid overtreatment.

View: Supplementary tables: Syphilis test characteristics and Syphilis serology interpretation. Accessed June 24, 2020.

Clinical stages of disease

Serologic tests, combined with the clinical history, are used to determine the stage of infection, which then dictates appropriate treatment.

Early syphilis is divided into three categories1:

- Primary – patients may present with a painless chancre at the site of inoculation. This phase is often clinically asymptomatic, and the ulcer will heal within weeks, even without treatment. If tested, serology may be non-reactive, and it must be repeated if there is suspicion of primary syphilis.

- Secondary – will occur in roughly 25% of patients with untreated primary syphilis, and manifestations may include a diffuse maculopapular rash involving the palms and soles, fever, and lymphadenopathy.

- Early latent – defined as asymptomatic infection with syphilis, as determined by serology, within the first year after infection. If prior serology is not available to confirm that infection dates back less than one year, patients should be considered to have late latent syphilis.

All stages of early syphilis are treated with IM penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units)3, long-acting formulation, divided into two doses of 1.2 million units each, administered in the right and left ventrogluteal sites.

Late syphilis is divided into two categories:

- Late latent – asymptomatic infection with syphilis, with time of infection greater than one year (or unknown).

- Tertiary – cardiovascular disease (aortitis), cutaneous gummas, and neurosyphilis are the clinical manifestations of tertiary syphilis. All patients with tertiary syphilis must undergo lumbar puncture to exclude neurosyphilis.

Late latent disease, or cardiovascular/gummatous disease without neurosyphilis, are treated with three weekly doses of IM penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units)3, long-acting formulation, each divided into two doses of 1.2 million units each, administered in the right and left ventrogluteal sites.

Neurosyphilis is treated with 14 days of aqueous penicillin G IV (IM therapy used for other forms of syphilis is not adequate, as it does not reach high enough concentrations in the central nervous system)3. Patients presenting with eye or ear symptoms may also have neurosyphilis, or require IV treatment, and should be assessed for this.

What I recommend

- Have a low threshold to perform STI testing in individuals at risk

- When ordering a syphilis screen, the lab will automatically do certain tests, so you do not need to specify – you can just order “syphilis EIA”

- For individuals being tested or treated for syphilis, make sure to test for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HIV

- Remember that treponemal tests will generally stay positive for life in individuals with previously treated syphilis

- Patients with previously treated syphilis, and who are re-infected with syphilis, will have an increase in their RPR titre

- Clinically and serologically stage syphilis in order to provide appropriate treatment

- Liaise with BCCDC STI physicians and nurses for questions about diagnosis, treatment, and follow up for patients with syphilis (604)-707-5600

Resource:

View or download: Supplementary tables: Syphilis test characteristics and Syphilis serology interpretation. Accessed June 24, 2020.

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Section 5-10: Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections- Management and treatment of specific infections – Syphilis. (View). Updated January 22 2020. Accessed February 12 2020.

- Provincial Health Services Authority. Interim Guideline on Syphilis Screening in Pregnancy. (View). Published September 2020. Accessed February 12 2020.

- BCCDC Clinical Prevention Services. Syphilis (Reportable). (View). Updated July 2016. Accessed February 12 2020.

Good morning, Dr. Naiditch – yes, I have read the same about approximately 30% of primary syphilis cases being bacteremic, especially when the lesion has been present for an extended period, or in the cases of recurrent primary syphilis. Unless I’ve missed something in the literature of the past few decades, conducting an LP to facilitate CSF studies in neurologically asymptomatic cases is no longer the standard of care, and speaking anecdotally, I do not recall a single incidence of a primary care or other provider doing the same. You’re probably aware, but roughly only a third of untreated patients with syphilis will go on to develop neurological or late syphilis complications. Our local HIV specialty providers often over-prescribe (?) out of an abundance of caution and treat their early (and late) syphilis patients with BIC 2.4mu x three weeks, just to make sure, even our pediatric HIV specialists. I, too, have observed an increased likelihood in HIV patients of developing neurological complications years after their primary or secondary infections, most especially when they have been treated for syphilis multiple times. Why is that? I don’t have the resources to explain it, either. Regarding using doxycycline to treat syphilis in the hopes that it will penetrate the BBB more effectively than the BPCNG, I offer that CDC’s STD Treatment Guidelines no longer even lists doxycycline as an “alternative” treatment for any stage of syphilis, excepting for a patient who is truly allergic to PCN, or in times of PCN shortage. During the recent global/national shortage of BPCNG, our health department, correctional facilities, and some other providers (not to mention other practitioners across our country) used a single dose of LA Bicillin 2.4mu and doxycycline 100mg twice daily for 28 days to treat apparent late latent syphilis cases where the RPR was 1:32 or higher. That way, the single dose of PCNG would actually treat/cure the infection if it was really a case of early syphilis, but the doxy x 28 days would take care of it if it was actually a late latent case. I hope all of that helps.

Thank you for the article and comment section – Extremely helpful. I have some interesting serologies; case presents to neurology w/ altered mental status. They test only RPR titer, which is 1:16. I request TPPA and repeat RPR 2 weeks later when I become involved. TPPA is N/R and RPR has now raised to 1:32. I asked case to be referred to ID for further eval, but I am curious if you think this could be syphilis (and concerns for neuro as well)? Or possibly something else triggering the titer?

The TPPA reacts specifically to the syphilis bacteria, so if it’s repeatedly nonreactive, that generally means that syphilis is not involved…as it’s simply not there. The RPR can react to some of the surface elements of the syphilis bacteria, but in large part, it reacts to the inflammatory response of whatever is going on. Further, the TPPA is highly specific and also unlikely to react when it shouldn’t. Something is clearly going on with your patient, but it’s not likely to be related to syphilis.

Hi Scott,

Have a patient, tested positive for CMIA and negative for RPR in Mar 2024, do another test in Apr RPR negative, EIA: positive, RPR negative. Did another test in May, CMIA positive, RPR negative, TPPA negative. Tested again in Jun and Aug 24 both test result in CMIA positive, RPR negative, TPPA negative. Did another test in Mar 2025, CMIA positive, RPR negative, TPPA negative. What should be the analysis? Advise to treat or not to treat? Thanks.

Hello Alun –

Your situation is similar to the one I addressed just above this one…. The TPPA reacts specifically to the syphilis bacteria…and you have three nonreactive TPPA tests on this patient spanning a timeframe of about 10 months. The CMIA and EIA are clearly reactive for other reasons. With the TPPA consistently nonreactive, you can be assured that the patient does not have syphilis and does not need to be treated for syphilis.

Hi Scott,

Any possibility of neurosypilis as patient complains of numbness and tingling on hand and feet. Patient also tested negative for HIV. Thanks.

Hello again Alun –

The repeatedly nonreactive TPPA results preclude a neurosyphilis diagnosis. If the bacteria were in the body causing neuro symptoms, the TPPA would be reactive…so the neuropathy couldn’t be related to syphilis, as the patient has three nonreactive TPPA results.

Would it still be possible for a patient to have syphilis who had two non-reactive RPR with reflex titer test results (about five months apart) as well as one non-reactive TPPA test result all 4-5 years after possible exposure?

I have a male patient who reported a low-risk exposure for syphilis (brief oral-genital contact, few seconds of glans penis licking, without ejaculation or penetration). The patient is highly anxious, so for peace of mind, I arranged two hospital-based CLIA total antibody tests:

– First test at 27 days post-exposure – negative

– Second test at 42 days post-exposure – also negative

The patient has remained completely asymptomatic (no chancre, no induration, no rash, no lymphadenopathy) and physical examination has been unremarkable throughout.

In our setting, presumptive treatment is not routinely administered for low-risk situations such as this.

Given the nature of the exposure, the absence of clinical signs, and the negative serology at two well-timed intervals, would you consider the case closed? Or would you still recommend follow-up serology (e.g., RPR/TPHA at 12 weeks) despite the very low pre-test probability?

Hey Scott,

I have someone who has repeated negative TPPA at 17, 19, and 37 days post exposure. The RPR was 1:4 and 1:2 at 19 and 37 days. What is going on here? They came in with a small crater like “lesion” but no active head, induration, or pain. Is it possible HSV could cause the RPR reactivity here?

Hello Mark –

Yes, the most important results here are the repeatedly nonreactive/negative TPPAs. That test most often reacts before the RPR, as it’s reacting directly to the bacteria, while the RPR is mostly reacting to the inflammatory process, which is/can be significant enough during an likely HSV outbreak to cause the titers of 1:4 and 1:2. Were you able to either culture the lesion for HSV or do a PCR swab? Those analyses might help to identify the pathogen during the first few days of the outbreak…and the PCR could even detect Treponema pallidum in the fresh lesion. Hope that helps.

To K:

Regarding your note: “Would it still be possible for a patient to have syphilis who had two non-reactive RPR with reflex titer test results (about five months apart) as well as one non-reactive TPPA test result all 4-5 years after possible exposure?”

The nonreactive TPPA 4-5 years post exposure is definitive…the patient did not contract syphilis during that exposure 4-5 years ago.

To Jean regarding your note:

“I have a male patient who reported a low-risk exposure for syphilis (brief oral-genital contact, few seconds of glans penis licking, without ejaculation or penetration). The patient is highly anxious, so for peace of mind, I arranged two hospital-based CLIA total antibody tests:

– First test at 27 days post-exposure – negative

– Second test at 42 days post-exposure – also negative

The patient has remained completely asymptomatic (no chancre, no induration, no rash, no lymphadenopathy) and physical examination has been unremarkable throughout.

In our setting, presumptive treatment is not routinely administered for low-risk situations such as this.

Given the nature of the exposure, the absence of clinical signs, and the negative serology at two well-timed intervals, would you consider the case closed? Or would you still recommend follow-up serology (e.g., RPR/TPHA at 12 weeks) despite the very low pre-test probability?”

In the USA, we use CDC’s STD Treatment Guidelines to determine if a person should be treated after an exposure to syphilis. Your notes are excellent in describing the exposure…but what appears to be missing is whether or not there was a syphilis lesion on the penis at the time of the very brief contact. CDC’s STD Treatment Guidelines encourages appropriate preventive treatment if the exposure was in the 90 days prior to testing…so the nonreactive tests are reassuring, but if your patient is not going to be preventively treated, he should certainly have another test 90 days after exposure (the maximum incubation period) to ensure that he wasn’t actually infected.