By Dr. Matthew Clifford-Rashotte (biography, no disclosures) and Dr. Natasha Press (biography and disclosures)

What frequently asked questions I have noticed

A 25-year-old man presents to your clinic for routine sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing. He has no symptoms nor known contacts with STIs. He has a history of previously treated syphilis, but is otherwise well.

His syphilis serology results are as follows: Syphilis EIA positive, RPR negative, TP-PA positive.

How should these results be interpreted?

We frequently encounter questions about the interpretation of syphilis serology and about the appropriate treatment of various clinical stages of syphilis.

Data that answers these questions/gaps

Syphilis rates have been rising in British Columbia, and across Canada, since the early 2000s1. In order to control this epidemic, clinicians must test at-risk patients, and interpret tests correctly in order to provide appropriate treatment. Interpretation of syphilis serology can be challenging, and misinterpretation may result in undertreatment or overtreatment, depending on the context.

When to test

Rising syphilis rates call for an urgent scale-up in testing. Potentially symptomatic patients (genital ulcer, rash involving palms and soles, or unexplained cranial nerve abnormalities, meningitis, etc.) should all be tested. Testing should also be performed in key groups of asymptomatic individuals:

- Pregnant women (both during the first trimester, and again at time of delivery – see below)

- Sexually active gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM)

- People with multiple sexual partners, those engaging in sex work, and those with symptoms of, or being tested for, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- People living with HIV

In the first half of 2019, two cases of congenital syphilis were reported in British Columbia, the first cases since 2013. As a result, the BCCDC has released an interim guideline2 recommending testing during two timepoints in pregnancy – during the first trimester or at the first prenatal visit, and again at the time of admission for delivery, or at 35 weeks for those who will not be giving birth in a hospital.

Interpreting test results

Serologic tests for syphilis are divided into two categories1:

- Treponemal tests, like syphilis EIA and TPPA, detect syphilis-specific antibodies. Once an individual has been infected with syphilis, these tests will usually remain positive for life, and thus they are no longer useful in distinguishing new versus prior infection.

- Non-treponemal tests, like RPR and VDRL, detect antibodies to cellular components released during tissue damage caused by syphilis. As a result, they are less specific, and can be elevated due to other conditions, including autoimmune diseases or acute febrile illnesses. These tests are reported as titres, which are used to monitor response to treatment or to ascertain reinfection in people with positive treponemal tests. With or without treatment, non-treponemal test titres will decline over time.

Historical testing algorithms for syphilis employed a two-stage approach, first by screening with a non-treponemal test, then performing a treponemal test for confirmation. Contemporary “reverse” screening algorithms, employed in British Columbia and in many other jurisdictions, screen first with an EIA (treponemal test), then perform an RPR (non-treponemal test) if positive, usually followed by an additional treponemal test (e.g. TP-PA) for further confirmation. Because non-treponemal tests take longer to turn positive in early infection and decline over time even in untreated individuals, screening with treponemal tests first is a more sensitive approach.

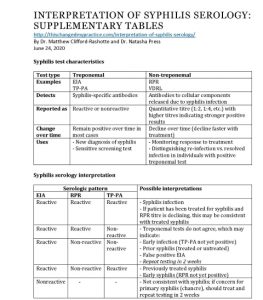

Here are some examples of common serologic patterns and their interpretation:

- EIA reactive, RPR reactive, TP-PA reactive

This is consistent with syphilis infection. If the patient has previously received treatment and the RPR titre is declining, it may be consistent with treated syphilis. - EIA reactive, RPR reactive, TP-PA non-reactive, OR

EIA reactive, RPR non-reactive, TP-PA non-reactive

The treponemal tests do not agree. This may be due to early infection where TP-PA has not yet developed, prior syphilis (treated or untreated), or potentially a false positive EIA. This patient should be re-tested in 2 weeks. - EIA reactive, RPR non-reactive, TP-PA reactive

Remember that treponemal tests will generally stay positive for life, so if the patient has previously been treated for syphilis, this is the expected serologic result. If the patient has never been treated, this could also be consistent with late latent syphilis, as RPR titres decline over time, with or without treatment. Confirming treatment history in this situation is essential to avoid overtreatment.

View: Supplementary tables: Syphilis test characteristics and Syphilis serology interpretation. Accessed June 24, 2020.

Clinical stages of disease

Serologic tests, combined with the clinical history, are used to determine the stage of infection, which then dictates appropriate treatment.

Early syphilis is divided into three categories1:

- Primary – patients may present with a painless chancre at the site of inoculation. This phase is often clinically asymptomatic, and the ulcer will heal within weeks, even without treatment. If tested, serology may be non-reactive, and it must be repeated if there is suspicion of primary syphilis.

- Secondary – will occur in roughly 25% of patients with untreated primary syphilis, and manifestations may include a diffuse maculopapular rash involving the palms and soles, fever, and lymphadenopathy.

- Early latent – defined as asymptomatic infection with syphilis, as determined by serology, within the first year after infection. If prior serology is not available to confirm that infection dates back less than one year, patients should be considered to have late latent syphilis.

All stages of early syphilis are treated with IM penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units)3, long-acting formulation, divided into two doses of 1.2 million units each, administered in the right and left ventrogluteal sites.

Late syphilis is divided into two categories:

- Late latent – asymptomatic infection with syphilis, with time of infection greater than one year (or unknown).

- Tertiary – cardiovascular disease (aortitis), cutaneous gummas, and neurosyphilis are the clinical manifestations of tertiary syphilis. All patients with tertiary syphilis must undergo lumbar puncture to exclude neurosyphilis.

Late latent disease, or cardiovascular/gummatous disease without neurosyphilis, are treated with three weekly doses of IM penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units)3, long-acting formulation, each divided into two doses of 1.2 million units each, administered in the right and left ventrogluteal sites.

Neurosyphilis is treated with 14 days of aqueous penicillin G IV (IM therapy used for other forms of syphilis is not adequate, as it does not reach high enough concentrations in the central nervous system)3. Patients presenting with eye or ear symptoms may also have neurosyphilis, or require IV treatment, and should be assessed for this.

What I recommend

- Have a low threshold to perform STI testing in individuals at risk

- When ordering a syphilis screen, the lab will automatically do certain tests, so you do not need to specify – you can just order “syphilis EIA”

- For individuals being tested or treated for syphilis, make sure to test for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HIV

- Remember that treponemal tests will generally stay positive for life in individuals with previously treated syphilis

- Patients with previously treated syphilis, and who are re-infected with syphilis, will have an increase in their RPR titre

- Clinically and serologically stage syphilis in order to provide appropriate treatment

- Liaise with BCCDC STI physicians and nurses for questions about diagnosis, treatment, and follow up for patients with syphilis (604)-707-5600

Resource:

View or download: Supplementary tables: Syphilis test characteristics and Syphilis serology interpretation. Accessed June 24, 2020.

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Section 5-10: Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections- Management and treatment of specific infections – Syphilis. (View). Updated January 22 2020. Accessed February 12 2020.

- Provincial Health Services Authority. Interim Guideline on Syphilis Screening in Pregnancy. (View). Published September 2020. Accessed February 12 2020.

- BCCDC Clinical Prevention Services. Syphilis (Reportable). (View). Updated July 2016. Accessed February 12 2020.

Succinct summary. Useful.

Great simplification if testing. Thanks, also a great reminder as to whom we should consider testing.

Hi – thank you so much for this very helpful summary. Just a note – the treatment for syphilis is IM penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units) LONG ACTING, divided into 2 doses (1.2 million units each) and injected into the R and L ventrogluteal sites. This formulation can be ordered directly from the BCCDC in pre-filled syringes, divided into the 2 doses. We’ve seen multiple cases of patients treated with a single injection and/or with the short acting formulation, resulting in inadequate treatment.

For reference: http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Communicable-Disease-Manual/Chapter%205%20-%20STI/CPS_BC_STI_Treatment_Guidelines_20112014.pdf

Excellent summary.

I was going to comment on the importance of specifying the divided dose of long acting, injected into both ventrogluteal sites (sometimes at the same time, if there is a second clinician available – as this can be more comfortable for the patient). But Chelsea has done a far better job of it.

I recommend that the authors be asked to edit to include this important detail in their TCMP write up, as not everyone reads these comments.

Thank you for your comments! We made two changes:

All stages of early syphilis are treated with a single dose of IM penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units)3.

CHANGED TO:

All stages of early syphilis are treated with IM penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units)3, long-acting formulation, divided into two doses of 1.2 million units each, administered in the right and left ventrogluteal sites.

Late latent disease, or cardiovascular/gummatous disease without neurosyphilis, are treated with three weekly doses of IM penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units)3.

CHANGED TO:

Late latent disease, or cardiovascular/gummatous disease without neurosyphilis, are treated with three weekly doses of IM penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units)3, long-acting formulation, each divided into two doses of 1.2 million units each, administered in the right and left ventrogluteal sites.

Thanks for this succinct and clear summary, extremely helpful. I’m wondering if you can comment on what a significant RPR titre rise might be in someone with previous infection that might alert you to re-infection. For instance, If someone’s titre is reduced to 1:2 after treatment and the it increases to 1:4 on a subsequent test, is that indicative of re-infection or would you see a larger increase? Granted I’m sure you need to factor in risk factors and symptoms, but I often see minor variation in RPR over time in those previously infected/treated and am unsure about interpretation.

Hello Nicholas,

Thanks for your question. An RPR rise of fourfold or greater (i.e. a change of two doubling dilutions, for example from 1:4 to 1:16, or 1:8 to 1:32) is considered clinically significant and would be consistent with reinfection. A minority of individuals will remain “serofast” despite appropriate treatment, meaning they will continue to have detectable low-level RPR antibodies. Most commonly, these are low-level (less than 1:8), and may demonstrate minor variation (a single dilution) over time. In the absence of an exposure, those in a serofast state with only a twofold change in titre would not be considered reinfected and would not require re-treatment. They should continue to be monitored over time.

Do you have an article or other document that provides a timeline or day by day progression of syphilis serologies converting from nonreactive to reactive…i.e.: how many days does it take for each to convert after infection….?

Patient has a history of RPR two-fold increases which 3 months later dropped again without treatment. Now patient has four fold from 1:2 to 1:8. Since it’s still “low-level” would this indicate reinfection or could be another rise which will later drop?

Every single syphilis case needs to be given Penicillin in to the vein. This is the only way to cure all forms of syphilis. The only way.

this might be a dumb question but if the patients number don’t rise but don’t decrease, staying exactly the same for example 1:20 to 1:20 every time he is tested, does that mean the number will never decrease? Will he ever have a negative result?

Can I ask if there is a correlation between the RPR titer and the TPHA titer? Thanks

To Huong Bui – The RPR titer is a measure of inflammation in the cells, which in this case is related to a syphilis infection. We can see a reactive RPR, sometimes even as high at 1:256, due to other inflammatory processes that have nothing to do with syphilis, as their confirmatory test (whichever ones are used) is nonreactive. The TPPA “titer” is only a measure of the strength of the body’s reaction to the presence of the syphilis organism itself, and once it’s reactive, it is of no further utility in a therapeutic sense…as it most often remains reactive for the life of the patient. The RPR will decrease on its own over time, even without the patient being treated, as the inflammation decreases with the natural quiescence or waning of the active disease process.

Are treponemal tests MORE or LESS likely to be reactive for life in untreated individuals? So if someone was worried about exposure say ten years ago and had symptoms, but their EIA, TPPA, CIA, FTA are all negative, is that conclusive? Or could there be false negatives due to length of time, other factors, ect

The treponemal tests are usually reactive for life whether the person was treated or not…like having a “scar” on the blood…the scar can fade over time, but usually endures. We have seen cases where the TPPA has become weakly reactive after a period of multiple decades since initial testing. In your case, if the confirmatory testing (with multiple types of test methods) is all negative and the possible exposure was ten years ago, I would be suspicious of the reported symptoms from back then, and be confident in the current nonreactive/negative results.

Scott, in that case because of the previous symptoms, would you treat? Or, would you say there’s no possible way for this many false negatives on these tests only ten years later.

Also, have you seen alcohol or antibiotics effect these tests? I know RPR/VDRL can be, but can treponemal?

Hello Dee – I would say that it is so incredibly unlikely that the patient actually had syphilis those many years ago because they have had numerous nonreactive Treponemal antibody tests since then…not just one nonreactive EIA or whatever, but from your earlier note, nonreactive EIA, CIA, TPPA, and FTA (we know the FTA is very sensitive and is prone to being a false positive). All of those specific antibody tests are nonreactive, so the patient very likely did not have syphilis symptoms…and treatment, I would not recommend it, no. Your lab testing repeatedly indicates the absence of syphilis.

If the patient is pressing for treatment, you might consider it. We have had some clinicians who will administer one dose of the Bicillin for a patient’s “peace of mind,” but certainly not three weeks of the injections; that’s a lot of PCN to dump into a body needlessly, time for everyone involved, and $ for the medication.

Regarding alcohol and antibiotics effecting the RPR/VDRL…it’s not likely, but a vaccination could…and also it would be very unlikely that alcohol and/or antibiotics could effect the Treponemal tests.

Actually to anyone here- if a patient said they had exact symptoms, years ago and didn’t realize, but had negative tests, would you treat empirically? Or would you believe it had to be a diff dx since it is the great imitator. Even if they tested so many years later.

It’s just all very confusing. they’re worried they tested too late and it’s not showing. I read some articles on pubmed about false negatives in late and tertiary but usually around rpr/vdrl but a few did pop up on trep specific tests. Maybe we should do the peace of mind shot or a course of doxy for peace of mind in case it was some other bacterial infection that wasn’t properly treated. They were also tested with ANA and RA and those came back negative as well as did Lyme. This is their first time testing for STDs since the encounter. As they thought they were at every routine checkup but weren’t. Ten years is a long time. Like you said at least one of these trep tests would have to show something

Patient tested positive in August 2022 and was treated with one single done of 2.4 penicillin, retested again in may 2023 FTA positive and RPR positive 1:2 (8 months)

Does that mean reinfected?

What was the patient’s RPR in 8/2022…and what stage of syphilis did the person have…was the single dose adequate for the stage? If the person did not have primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis, they should have received the BIC 2.4mu x three weeks with doses administered between 7/9 days apart.

The FTA-ABS will very likely remain reactive/positive for the rest of the person’s life. The RPR should go down fourfold (two dilution factors) within 12 months after treatment.

We can’t say they’ve been reinfected until we know something about their pre-treatment RPR….

Patient is a contact to syphillis. Had flu like symptoms after sex including a mouth sore. Doesnt want treatment unless they test positive themselves. EIA test is done 19 days after sexual encounter. Is that enough time to test positive or do they need to re-test. When does exactly EIA turn positive after the initial exposure?

The EIA results should be reactive 2-3 weeks after infection with syphilis, often before the appearance of the primary lesion…but that test does not differentiate between this being a new, old, or previously treated case. When was the person’s last syphilis testing, does he/she/they have sex with males or females (or other genders), does he/she/they use IV drugs? If the fever and flu-like symptoms occurred shortly after a sexual episode, I would ask when was the last previous sexual encounter with the same or different person? I would also be more inclined to suspect an acute HIV infection or some other viral syndrome. We generally observe fever and flu-like symptoms with syphilis cases in the latency period between primary and secondary symptoms and during the second stage of syphilis, not shortly after exposure.

Regarding the mouth sore, could that be an apthuous ulcer or HSV outbreak? Primary syphilis lesions can take 10-90 days to develop, but generally appear around 3-4 weeks after exposure to the other person’s syphilis ulcer. If the patient’s EIA is reactive and the subsequent RPR titer is low, I would encourage repeat treponemal testing with the TPPA, as it is much more specific than the EIA. The EIA could be a false positive if the patient has an acute HIV infection or other viral infection (like an initial HSV outbreak). However, if the RPR titer results are relatively high, you can be more confident in the reactive EIA results.

And regarding the patient not wanting treatment unless they test positive themselves, the goal is to prevent cases from occurring (obviously), so that preventive treatment is absolutely necessary. If the patient refuses treatment, they should abstain from all sexual contact (even protected) and repeat testing at a minimum of 90 days after the exposure.

Thank you, Scott. Two Syphilis EIA tests had been done so far for the client. First on Day 19 after sexual act (exposure), and second at day 39 after exposure. Both syphilis EIA tests are non-reactive. HIV tests also came back negative. EIA non reactive 39 days post exposure would suffice to rule out infection? or is there still a possibility that the test is not picking up the infection? Patient is agreeable to treatment but still would like to know for sure they have syphilis which we are not able to confirm with the tests. Thanks.

The EIA test should be reactive by now, but we cannot know for certain if the body’s always going to react as we predict it will. Here in the US, we use CDC’s STD Treatment Guidelines as our reference for testing and treating syphilis…and it recommends that all persons exposed to syphilis receive preventive treatment if their nonreactive test is within 90 days of that last exposure. I suggest that this is the safest, most conservative position to take, so if the patient is willing to receive the treatment, it would be a good idea to do so.

You’re welcome.

If a value of syphilis is reactive with a titer of 1:1 but the standard range non-reactive after 6 months and 3 doses of intra muscular penicillin am I cured or serofast? Also would I be contagious at this stage?

Patient tested Reactive for SYPH Jan 2021 , with a RPR 1:2 , was retested with a Reactive SYPH Feb 2021 but a Nonreactive RPR , and TPPA was Nonreactive . Patient continued to get tested Oct 2021 , Aug 2022, Sep 2022, Feb 2023, May 2023 and SYPH was Reactive but the RPR was Nonreactive and TPPA was Nonreactive. Patient tested Aug 2023 : SYPH was Reactive , RPR was 1:1 and TPPA was Nonreactive. Patient was given 3 doses of 2.4 Bicillin for the 3 weeks for suggested treatment. Patients partner tested for SYPH and came back Negative , RPR Nonreactive, TPPA is Nonreactive. (Tested after the 90 day period) . What do you interpret patients test results? Why is patients partner not positive for SYPH?

Elly – your patient has repeatedly nonreactive TPPAs spanning more than two years, so he/she doesn’t have syphilis…the screening test and RPRs are false positives. The TPPA is more reliable than whatever screening TpAb, EIA or FTA test that is being used, so the patient is not infected…doesn’t have syphilis…which explains why the partner is not positive. Treatment is not warranted with repeatedly nonreactive TPPA testing.

Anthony – The RPR 1:1 is barely reactive…and you haven’t mentioned a syphilis treponemal antibody test. Was that reactive? We know that the longer a person has untreated syphilis, the longer it’s going to take for the RPR to revert to nonreactive, so even after proper treatment, the RPR may not decrease substantially. Also, we’re typically not concerned about the titer decrease until one year after treatment…in which we hope to see a fourfold titer decrease, which you’re not going to have, given that the RPR was only 1:1 to start. Lastly, having a reactive RPR does not make one contagious (it essentially measures inflammation); you would be contagious with a syphilitic lesion or other open skin manifestation (mucous patches, condylomata lata, etc.).

What tests should be run to determine why patient is having false positives for SYPH for the past two years and now an RPR 1:1? Patient has went to three different clinics with the same results , patient states that practitioner says they had an infection but the 2.4 Bicillin has decreased the infection, but again patients TPPA has always been Nonreactive.

Patient’s EIA Negative in India but EIA positive in Canada. RPR and TPHA negative. Hiv serology negative with screening in USA , India and Canada with PCR, Western Blot and screening tests. HCV PCR and antibodies negative. HBV Negative, MGen negative, HSV 1 and 2 negative and every antibodies Negative except H Pylori igG positive and SARS COV high antibodies spark. Patient has had no sexual contact in 13 months. But EIA for syphilis in Canada repeatedly positive. Patient has high igE and high Eosinophils to the tune of 6-13 observed. What could be the cause behind repeatedly reactive EIA in Canada?

Hello patient has had numerous sex partners in the past 6 years, Got tested for the first time almost 2 years ago everything negative. RPR non reactive, Patient worried RPR isnt picking up if he had late or tertiary syphillis he never noticed any symptoms in those years he decided to do a TPPA got treated just in case results negative, A year and half later does another RPR negative and TPPA negative, Would the negative TPPA conclude he never had syphillis since that test remains reactive for life?

Scott…..Patient’s EIA Negative in India but EIA positive in Canada. RPR and TPHA negative. Hiv serology negative with screening in USA , India and Canada with PCR, Western Blot and screening tests. HCV PCR and antibodies negative. HBV Negative, MGen negative, HSV 1 and 2 negative and every antibodies Negative except H Pylori igG positive and SARS COV high antibodies spark. Patient has had no sexual contact in 13 months. But EIA for syphilis in Canada repeatedly positive. Patient has high igE and high Eosinophils to the tune of 6-13 observed. What could be the cause behind repeatedly reactive EIA in Canada?

Hi I was wondering if a person has tertiary syphilis or maybe neurosyphilis, will a serology test like eia be able to detect syphilis? Chatgpt told me that the antibody might decline in tertiary stage. But again it won’t make sense to me as many individuals won’t know if they are in tertiary or not.

Ravi – I would have suggested any of the above as possible causes for the EIA to be repeatedly reactive, and beyond those, other conditions known to cause false-positive EIA testing could be advancing age, substance abuse, recent/repeated vaccinations, thyroid problems…and others. To speculate further would be out of my arena, so I’ll stop there. The good thing, from what I understand in your note, is that the TPHA is negative, so you can be confident that the person doesn’t and hasn’t had syphilis.

Yes, Carlos, the repeatedly nonreactive RPR and TPPA testing are good indicators that the patient was not infected with syphilis from any of the multiple partners.

James…a person with tertiary/late/neurosyphilis will likely have an elevated RPR due to the inflammatory processes of whatever condition they’re experiencing to be diagnosed with this stage of syphilis, and their TpAb testing will also be reactive. If you’re simply referring to late latent syphilis, no they’re not having any symptoms, but their TpAb testing would also likely be reactive. We’ve had many cases of people treated for primary or secondary syphilis 20-30 years ago and their TpAb test is still reactive.

Patient has previously been tested yearly for syphilis and EIA always negative. This year EIA reactive but prp and TPPA negative. Restated patient 2-3 weeks and EIA now says “EQUIVICOL” however, rpr and TPPA still negative. What is the interpretation?

New to treating syphilis. I am quite confused by where syphilis total AB falls into place – I am seeing a guy who engages in high risk behaviors, has consistently had syphilis total AB of >8.0, with RPR reactive, and RPR titer has decreased over the last 5 years from 1:128, 1:2 (3 years ago), 1:32 (8 months ago- incorrectly treated with Bicillin LA 1.2 mill units IM x 1) and now 1:4 two weeks ago – – how do I interpret this? The Syphilis total AB test result is tripping me up some. for reference he is HIV negative, on PrEP

To Sara –

The TPPA is a much more specific test than the EIA, so I would rely more heavily upon those results than the EIA results. From what you’ve shared, the patient does not have syphilis.

To Gretchen –

Your patient had f/u RPR 1:2 three years ago and then 1:32 eight months ago, but was incorrectly treated with BIC 1.2mu. If there were no symptoms present when the RPR was 1:32 and no testing between the 1:2 three years ago and the 1:32 eight months ago, we should assume that the patient has a “new” case of syphilis of unknown duration or late latent syphilis, so even with the decrease in titer to 1:4 after the incorrect treatment of Bicillin LA 1.2mu, he needs to be restarted on correct treatment of BIC 2.4mu x three weeks. The titer usually decreases over time even without treatment, so don’t be confused by the 1:4 after the incorrect treatment. He still needs appropriate treatment x three weeks.

Hello

03/07/24

I have a patient who was treated for syphilis with rpr of 1:2, was treated with PCN G IM for early syphilis, 9 months after treatment is rpr titer was non reactive, 3 months later his RPR titer is 1:2 would he be considered serofast or does he need to be treated, patient is without symptoms.

Hello,

One patient has syphilis exposure about 3 months before tested CMIA reactive, RPR negative and TPPA negative. Another subsequent test was taken 2 weeks after the first test. 2nd test was also the same as the 1st test, patient show no signs of rashes but complained of back ache body feeling warm and chill. The patient have no prior syphilis and also treatment of syphilis history. What would be the interpretation?

To Alun –

Could you please tell me what the CMIA index is? I also have a similar case

Hi,

My patient had oral sex with someone (who tested negative on CMIA 5 weeks later). After 5 weeks, my patient tested with CMIA result of 1.28 s/co, TPHA negative, RPR negative. Two weeks later, the test result remained the same as the first time. My patient has never had syphilis before. How do you explain these results?

Literature available online indicates that a CMIA index greater than 1.0 is indicative/suggestive of a current or previous syphilis infection; however, when a patient has negative/nonreactive TPHA testing in conjunction with the reactive CMIA testing, we would default to the TPHA results, as that test is more specific than the CMIA. As noted in earlier comments in this thread, the TPPA/TPHA would become reactive within three weeks of actual infection with syphilis. I would suggest repeating the TPHA testing in another few weeks to confirm the earlier nonreactive test and then look for a different cause of the reactive CMIA test…something that’s likely causing the body aches and intermittent fever.

To Alun –

If the TPPA/TPHA remains nonreactive more than 90 days after exposure to a known syphilis case (and no other exposures since that date) you can consider the CMIA to be a false positive. The presence of actual syphilis would have caused the TPHA to be reactive by now.

Hi

Is a negative RPR and negative TPHA test result at 9 weeks post-exposure sufficient to conclude?

CDC’s STD Treatment Guidelines recommends that anyone exposed to syphilis within the 90 days prior to their negative testing should be preventively treated, given that 90 days is the maximum incubation period for syphilis…while some non-public health practitioners will sometimes not treat if the nonreactive testing is at least 21 days after exposure, as that is the average incubation period. Not sure what your guidelines are in your country, but I would encourage you to preventively treat your patient while you have the opportunity, as the patient may not return at the 90 days post-exposure timeframe for repeat testing. Keep in mind, also, that we prefer to prevent cases…not to wait until the person has a reactive test to finally treat them. Who knows how many people they could have infected during the interim.

I have read that approximately 33% of patients with primary syphilis are bacteremic, but have also read that bicillin poorly penetrates the BBB (blood brain barrier). Meaning that our use of bicillin doesn’t necessarily treat asymptomatic CNS syphilis. Is doxcycline a better choice, esp. in patients with HIV? I have seen patients who were HIV positive who were properly treated who then ended up years later with CNS illness, in the absence of a recurrent illness and no change in testing. What is the data on this?

Is there any indication to use doxy in addition to Bicillin in any situation? Appreciate your thoughts