Author

Shirley Samuel-Haynes MD CCFP FCFP (COE) (biography, no disclosures)

What I did before

I knew Serious Illness Conversations (SIC) were important and patients valued them. I had challenges having SIC with patients and their families. I did not have a good model to follow. I confused Goals of Care (GOC) with SIC. I would describe to patients the care goal categories (from resuscitative to medical to comfort) and then ask, “If you got really sick what do you want us to do?” Then if they chose a care goal I did not feel was reflective of their prognosis, I am sure my body language communicated my disapproval adding a silent schism to the relationship.

Sometimes after the patient and I would agree on a level of care, I would encourage them to discuss the decision with their families — only for the patient to return and request a higher level of care after this discussion. Again, I am sure my body language expressed my confusion and disappointment adding schism to the relationship while I changed the GOC order.

Worse — I would be annoyed if the patient (usually at the end stages of their diagnosis) refused to have these discussions or accused me of wanting them to pursue Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID). The threat stress responses, bias, and the accompanying body language destroyed the relationship when they needed a trusted physician the most.

I saw the need for the conversations and dreaded having them. I required a different approach.

What changed my practice

The first resource that changed my practice was Pallium Canada,1 a national, non-profit organization focused on building professional and community capacity to help improve the quality and accessibility of palliative care in Canada. They have a few free online courses regarding SIC that started the improvement in my practice.

With Pallium I learned about a virtual training program called Community Access to Palliative Care via Interprofessional Teams Intervention (CAPACITI) and I developed a palliative approach to care (recognizing this is not palliative care).2 The CAPACITI program consisted of 3 modules and each module had 4 one-hour sessions that I completed every 2 weeks. The first module was about identification of patients who would benefit from the palliative approach to care. The second module was about communication. The third module was about connecting with community resources and partnering with caregivers.

I learned that a palliative approach to care addresses and manages patients’ and families’ psychological, practical, social, loss/grief, spiritual, and physical issues like pain and symptom management in line with their GOC and helps prepare for eventual life closure. It aims to actively treat all issues that arise and proactively address other issues including emergencies to manage them quickly and effectively if they do occur.

Any person living with an incurable illness (COPD, CHF, dementia, cancer, ALS, Parkinson’s) may benefit from a palliative approach to care that aims to provide comfort and improve quality of life through whole person-centred care. Receiving a palliative approach to care is not dependent on time left to live and many patients receive this care for months to years before death occurs.

Ideally, a palliative approach to care is started early in a patient’s illness trajectory (i.e., at the time of diagnosis of an incurable illness or as the illness starts to progress). CAPACITI shared research has found that those who receive an early palliative approach to care have improved quality of life, reduced anxiety, improved pain and symptom management, and often live longer.

What I do now

My confidence and attitude have changed. I moved away from a task-oriented mindset where the objective was to complete the GOC as soon as possible satisfying an organizational requirement. I am better at suspending my agenda and following the patient’s lead. I view these conversations as a chance to get to know the patient and their families better. I approach SIC in steps and accept that it may be done over a few visits.

Identification

There are objective tools such as the READ code, Clinical Frailty Scale, Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT), and the Mississauga Halton Palliative Care Network Early Identification and Prognostic guide that can help identify patients who would benefit from the palliative approach to care. The simpler intuitive tool of the Surprise Question (Would you be surprised if this patient were to die in the next year?) is easier and is as effective at identification. Incidents such as new life-limiting diagnosis, recent hospitalization, specialist visit, change in function or medication can also serve as potential identifiers.

Billing

In Alberta (and most provinces), there are no specific billing codes for SIC and GOC. SICs require time and may be best done at the end of the day when the practitioner does not need to worry about the rest of the day. At the same time, these conversations require cognitive and emotional energy that may be decreased at the end of the day. The practitioner may need to experiment to find what best suits them.

If you have a team dedicated to this work, parts of the SIC can be done by other health-care team members such as exploring the patient’s illness understanding, goals, and values, or updating the families. Education should be provided for team members with the understanding they will be using these skills to participate in these conversations. Physicians and nurse practitioners complete the GOC order. The staff can educate the patient and their families about where to keep the order for easy access during emergencies while ensuring there is a GOC order in the chart. (This is a requirement if the patient lives in a facility in Alberta.)

As for billing, I use the palliative billing codes. They are in 15-minute time increments. Include the start and end times. In Alberta, the code is 03.05I while in the office.

Billing in BC:

- Billing guides. Family Practice Service Committee BC. Accessed Oct 31, 2023. (View)

- Fees billable by the Community Longitudinal Family Physicians (CLFPs) who have submitted 14070 or 14071 for locums:

- Palliative Billing Guide 14063. Updated February 4, 2022.

- Complex Care Planning and Management 14033, 14075. Updated February 4, 2022.

- Mental Health Billing Guide14043. Updated February 4, 2022.

- Fees billable by the Community Longitudinal Family Physicians (CLFPs) who have submitted 14070 or 14071 for locums:

- The Longitudinal Family Physician (LFP) Payment Model. Ministry of Health. Updated November 21, 2023. Accessed November 22, 2023. (View)

Preparation

When making space and time for this conversation, invite the patient to identify people they want to be involved in the conversation. Involving caregivers early is a key step I was missing earlier. Educate yourself on the patient’s illness. Likely there will be questions about trajectory and prognosis by the patient and their families during this conversation. Ideally, specialists provide this information to patients during their visits too.

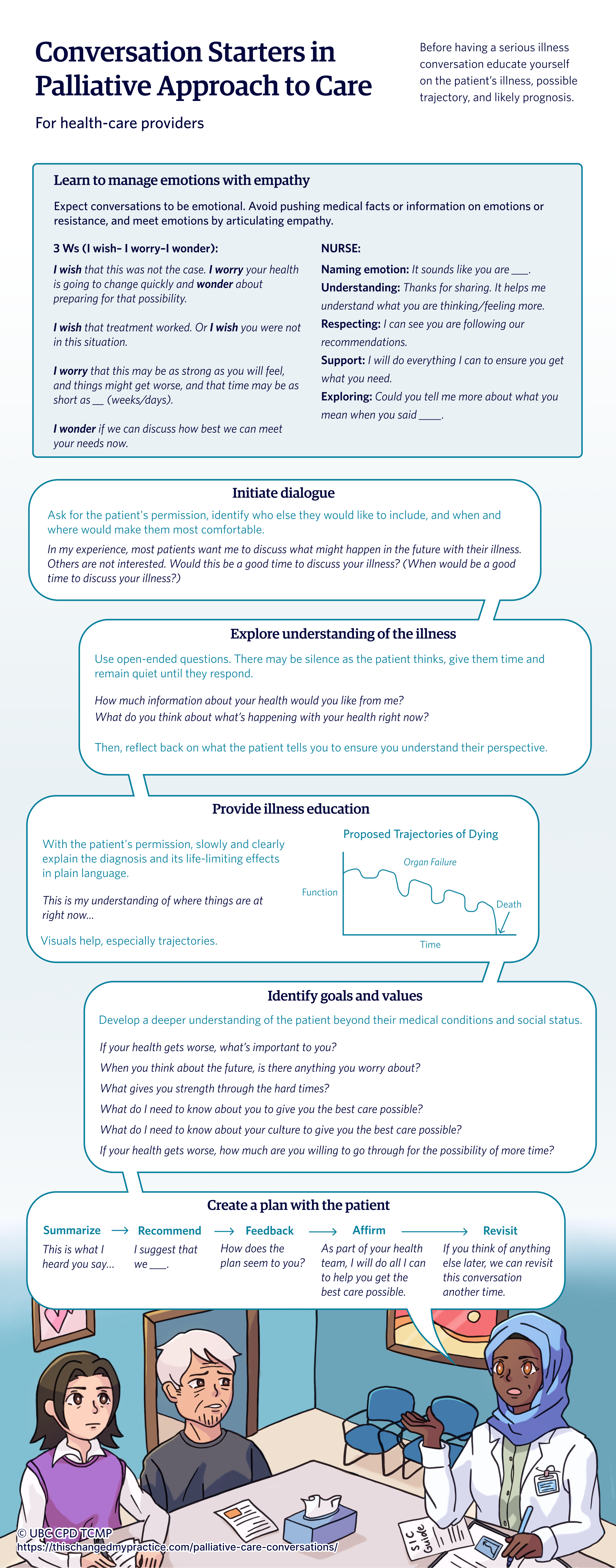

Initiate dialogue

Ask for the patient’s permission, identify who else they would like to include, and when and where would make them most comfortable.

Conversation starters:

“In my experience, most patients want me to discuss what might happen in the future with their illness. Others are not interested. Would this be a good time to discuss your illness? (When would be a good time to discuss your illness?)”

Explore patient’s illness understanding

This step is important to avoid misunderstandings. There may be silence as the patient thinks. Remain quiet until they respond. Use open-ended questions. Reflect back on what the patient tells you to ensure you understand their perspective.

Conversation starters:

“What do you think about what’s happening with your health right now? How much information about your health would you like from me?”

Provide illness education

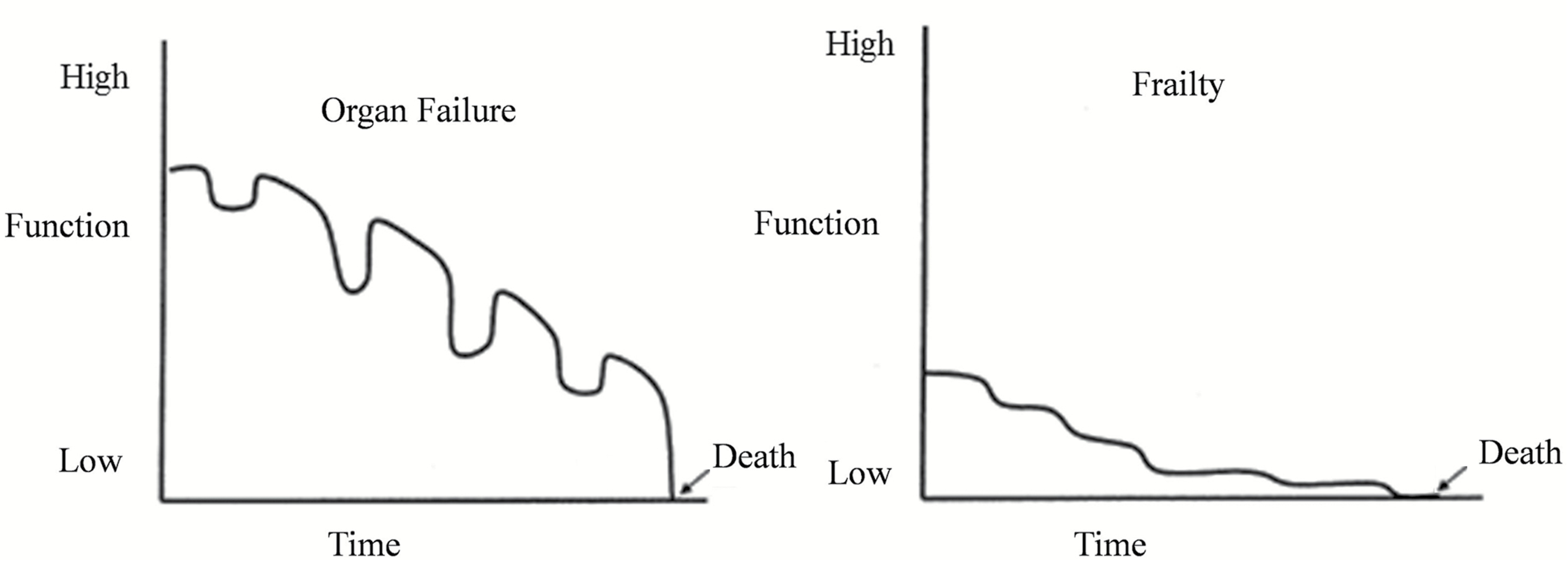

According to Health Canada, up to 70% of patients, do not understand that their serious illness cannot be cured and will progress over time.5 With the patient’s permission, slowly and clearly explain the diagnosis and its life-limiting effects in plain language. Visuals help, especially trajectories, see Figure 1. In my case, it is usually the organ failure or frailty trajectories that are used often.

A helpful guide on timelines: after noting how much they change in specific periods, that time frame can be used to predict timelines such as days to weeks or weeks to months. Also, with the patient’s permission, pointing on the graph where I think the patient’s status is at is helpful at gaining mutual understanding about the illness and timelines.

Conversation starters:

“This is my understanding of where things are at right now.”

Figure 1. Trajectories of Dying

From Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C. Profiles of older medicare decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6):1108-1112. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50268.x

Emotions

Expect these conversations to be emotional. There may be resistance to these conversations too. Avoid pushing medical facts on emotions or on resistance. Meet emotions with empathy. This was an important lesson for me. NURSE (Naming, Understanding, Respecting, Supporting, Exploring) statements help articulate empathy. I am also finding that exploring statements of empathy help examine replies that surprise me or on the surface seem like an attack. Use of the Three Ws (I wish– I worry–I wonder) will also help.

Conversation movers:

NURSE:

- Naming emotion: “It sounds like you are ___.”

- Understanding: “Thanks for sharing. It helps me understand what you are thinking/feeling more.”

- Respecting: “I can see you are following our recommendations.”

- Support: “I will do everything I can to ensure you get what you need.”

- Exploring: “Could you tell me more about what you mean when you said ____.”

Three Ws (I wish– I worry–I wonder):

- “I wish that treatment worked.” Or “I wish you were not in this situation.”

- “I wish that this was not the case. I worry your health is going to change quickly and wonder about preparing for that possibility.” Or “I worry that this may be as strong as you will feel, and things might get worse, and that time may be as short as __ (weeks, days).”

- “I wonder if we can discuss how best we can meet your needs now.”

Explore patient’s goals and values

This has become the most interesting part of the conversation and themes of care goals emerge. According to Health Canada, there is clear evidence that values and goals guide as few as 10% of clinician recommendations.5 Key topics such as goals, fears, sources of strength, critical abilities, and trade-offs are explored. Here I ask the dignity question and some experts advocate modifying this question to explore worldviews/culture regarding the life-limiting illness. I am finding I am developing a deeper understanding of the patient beyond their medical conditions and social status at this point of the conversation.

If the family is not present during this visit, I will ask the patient if their family is aware of their wishes. If not, I will ask the patient if they want me to share the details of this conversation with them at another visit or do they want me to call the family. Preferably family participates during a visit. There are times the patient prefers I call their family. I have spoken to family members about the SIC over the phone at another time. The caregiver appreciates this extra step. This act has also decreased the requests to change the GOC order after family discussions.

Another important lesson for me was accepting that all the steps for this conversation are likely not going to happen during one visit. Pay attention to your feelings too. If you are feeling impatient, use it as a queue to schedule another visit.

Conversation starters:

- Goals: “If your health gets worse, what’s important to you?”

- Fears & worries: “When you think about the future, is there anything you worry about?”

- Sources of strength: “What gives you strength through the hard times?”

- Dignity: “What do I need to know about you to give you the best care possible?”

- Culture: “What do I need to know about your culture to give you the best care possible?”

- Critical abilities: “If your health gets worse, how much are you willing to go through for the possibility of more time?”

- If the family is not present: “Is your family aware about what is most important to you?”

Create a plan

Summarize the prognosis and the patient’s answers to the key topic questions. Then, with the patient’s permission, make recommendations. After making the recommendations, ask for the patient’s feedback. Document the recommendation by completing the GOC order and provide the patient with the original order keeping a copy for the chart. In Alberta, this order is kept in a green sleeve and on the fridge with a copy of the personal directive for ease of access in case of emergencies. This is a suitable time to affirm your commitment with the patient and their family. As the visit is ending ask the patient if there is anything more they want to add and remind them this conversation can be revisited at another time.

Conversation starters:

- Summarize: “This is what I heard you say…”

- Recommend: “I suggest that we ___.”

- Feedback: “How does the plan seem to you?”

- Affirm: “As part of your health team, I will do all I can to help you get the best care possible.”

- Revisit: “If you think of anything else later, we can revisit this conversation another time.”

Outcomes after practice change

I am now more comfortable having these conversations. I am prepared for serious illness conversations to be emotional and likely will take time upfront. This investment pays it forward in multiple ways in future clinical visits. I know my patient and their families better and am confident the health-care team and I are providing care that is aligned with the status of their illness and the patient’s and families’ values. Health Canada adds that most patients and their substitute decision-makers, who have conversations about serious illness, experience less anxiety when they understand the illness and how it will progress.5 They also add that outcomes are better, distress is less, and clinicians have greater professional satisfaction.

Resources for health-care providers

View and download the conversation starters handout you can use in practice. Download PDF: colour and black and white version.

- Samuel-Haynes S. Conversation Starters in Palliative Approach to Care Handout. UBC CPD. Accessed November 9, 2023. (View colour or black and white PDF version)

- Preparing for a serious illness conversation – a guide for health care providers. First Nations Health Authority. 2019. Accessed October 31, 2023. (View PDF)

- Palliative approach resources. CAPACITI. Accessed October 31, 2023. (View PDF)

Resources for patients

- Individuals & families. The Advance Care Planning Canada by the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (CHPCA). Accessed October 31, 2023. (View website)

- Your Care, Your Choices: guide to learning about advance care planning in BC. First Nations Health Authority. Accessed October 31, 2023. (View PDF)

- The Waiting Room Revolution Podcast. Accessed November 27, 2023. www.waitingroomrevolution.com/podcast

Hosts: Dr. Samantha Winemaker, palliative care doctor, and Dr. Hsien Seow, health-care researcher share real-life stories to explain the 7 keys to being hopeful and prepared when facing serious illness.

References

- Pallium Canada. Accessed October 31, 2023. (View)

- CAPACITI. Palliative Care Innovation. Accessed October 31, 2023. (View)

- Lowey S. Types and Variability with Illness Trajectories. In: Lowey S. Nursing Care at the End of Life. Open SUNY Textbooks; 2015. (View)

- Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C. Profiles of older medicare decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6):1108-1112. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50268.x (View with CPSBC or UBC)

- Fact sheet: 3 Questions to ask yourself that make difficult conversations about serious illness easier. Government of Canada. Accessed November 26, 2023. (View)

Excellent article. Thank you.

Lots of people talk about these issues. I think all of us want to be good at this!

What is different here is that you’ve given me PRACTICAL guidance on how to more effectively participate. Thank you.

Excellent guide to dealing with the big questions. I am 76 years old, retired FM. WIshing my own FMD might be capable of the empathy needed in using these cues.

I wish there was a way to get this article out to ALL medical practitioners – this approach makes such a difference to the illness experience of patients, families, and the health care team.

Outstanding article. I have done the Victoria Palliative Care course twice in the past 25 years and attended numerous talks on the subject but I found this the best one especially on technique approach on opening and carrying out discussions on SIC. I also facilitate Palliative Care seminars for first year medical students at SMP and will definitely be recommending that they read this article. Thank you for sharing.g

This is an excellent article, very informative and helpful for patients with terminal illness.

I work in a nursing home most of the residents suffer from different stages of dementia.

The Palliative approach to care conversation is excellent – unfortunately most of the conversations are with family.

Any suggestions on a palliative approach to care for these residents, as the focus is more on the family and their understanding of the resident’s illness and wishes?

Thanks for your comments and question Wiliam. Apologies for my late reply. I will do my best to answer.

I also work with people with major neurocognitive disorders at varying stages and in different living situations. From my experience, most people with major neurocognitive disorders and their families appreciate the palliative approach to care, especially learning about the prognosis and trajectory of the illness. I use the frailty graph above as the visual aid.

Early stage: Usually people in the early stages of major neurocognitive disorder are their own decision makers. Education and encouragement for planning are important at this stage of the diagnosis. The person with major neurocognitive disorder should be encouraged to involve family or their future substitute decision makers when having these conversations with their health team. They can give direction to their families about their current care and prefered care in the event of a health crisis.

This document can help: My Plan – ACP in Canada | PPS au Canada (advancecareplanning.ca). Usually at this stage, grief is present: anticipatory and ambiguous grief. The palliative approach to care provides space for grief. This resource helps guide the grieving journey: As illness progresses: Dementia, ALS, MS, Parkinson’s, or Huntington Disease: Introduction: Overview (mygrief.ca).

Moderate stage: Usually people in the middle or moderate stage of major neurocognitive disorder are not able to complete their instrumental activities of daily living, including arranging health visits and medication management. They are relying on family for these tasks. These people are likely to be the future substitute decision maker for the person with major neurocognitive disorder. Yet the person with major neurocognitive disorder is normally still their decision maker at this stage. Because both family and the person with major neurocognitive disorder are together for the health visits, this is an important time to repeat these conversations. Health teams can review care goals with the person with major neurocognitive disorder involving family and future decision makers as the diagnosis progresses. Caregiver stress usually increases at this stage too. The palliative approach to care provides space exploring caregiver stress and options to support the person with major neurocognitive disorder and their families.

Late stage: Usually people in the late stage of major neurocognitive disorder require assistance for their basic activities of daily living and are usually unable to be left alone. Most likely the person with major neurocognitive disorder has behaviour and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). I don’t think I do a good job of sharing with patients and their families the likelihood of BPSD. They are distressing for families. Usually BPSD leads to placement in formal settings for the person with major neurocognitive disorder. The person with major neurocognitive disorder is typically not involved or is minimally involved in their care decisions. If the person with major neurocognitive disorder had these conversations with their families/substitute decision makers before progression, these conversations can be used as a guide for future shared decision making by the families/substitute decision makers. At this stage the terminality major neurocognitive disorder is apparent. With the visual tool I mentioned earlier, I show families the person with major neurocognitive disorder is at the last stages. Grief and caregiver stress is still present and supported with the palliative approach to care. I find families/substitute decision makers normally comment, “I just want them to be comfortable” or “I don’t think they would want treatment that prolongs their lives.” The palliative approach to care supports families making these hard decisions by reviewing the best evidence while recalling the person with major neurocognitive disorder’s values while providing care that best meets both.

I hope I answered your question. Thanks!